Bergamot is one of many essential oils extracted from the outer peel of citrus fruit. It differs from other citrus oils by its chemical composition, and different therapeutic guidelines and safety precautions apply to it. This is especially true for safety limits to prevent phototoxic reactions due to the bergapten content of Bergamot oil (unless it is bergapten-free). It is therefore imperative to correctly distinguish Bergamot oil from that of other citruses. However, there is currently no consensus on what actually is the correct botanical name for Bergamot.

Bergamot is one of many essential oils extracted from the outer peel of citrus fruit. It differs from other citrus oils by its chemical composition, and different therapeutic guidelines and safety precautions apply to it. This is especially true for safety limits to prevent phototoxic reactions due to the bergapten content of Bergamot oil (unless it is bergapten-free). It is therefore imperative to correctly distinguish Bergamot oil from that of other citruses. However, there is currently no consensus on what actually is the correct botanical name for Bergamot.

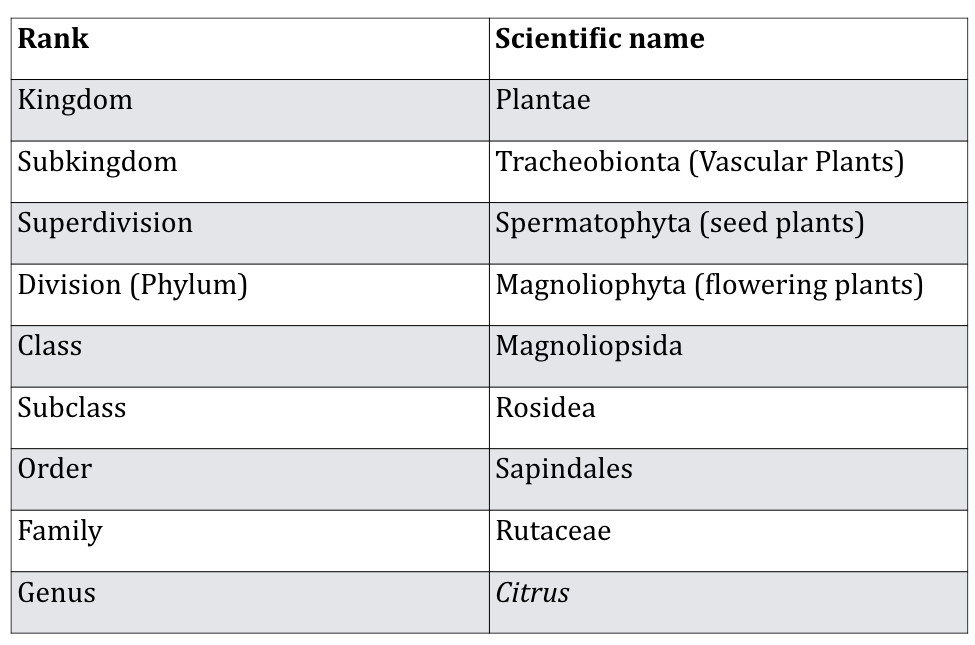

It is important to identify the specific plant that produces an essential oil by its scientific name, also known as binomial. In aromatherapy a binomial is often referred to as the botanical name of a plant. Essential oils from plants with similar common names are sometimes extracted from different species, which produce essential oils with different constituents and therapeutic guidelines. There are also many essential oils produced from closely related plant species, such as the essential oils from the Citrus genus.

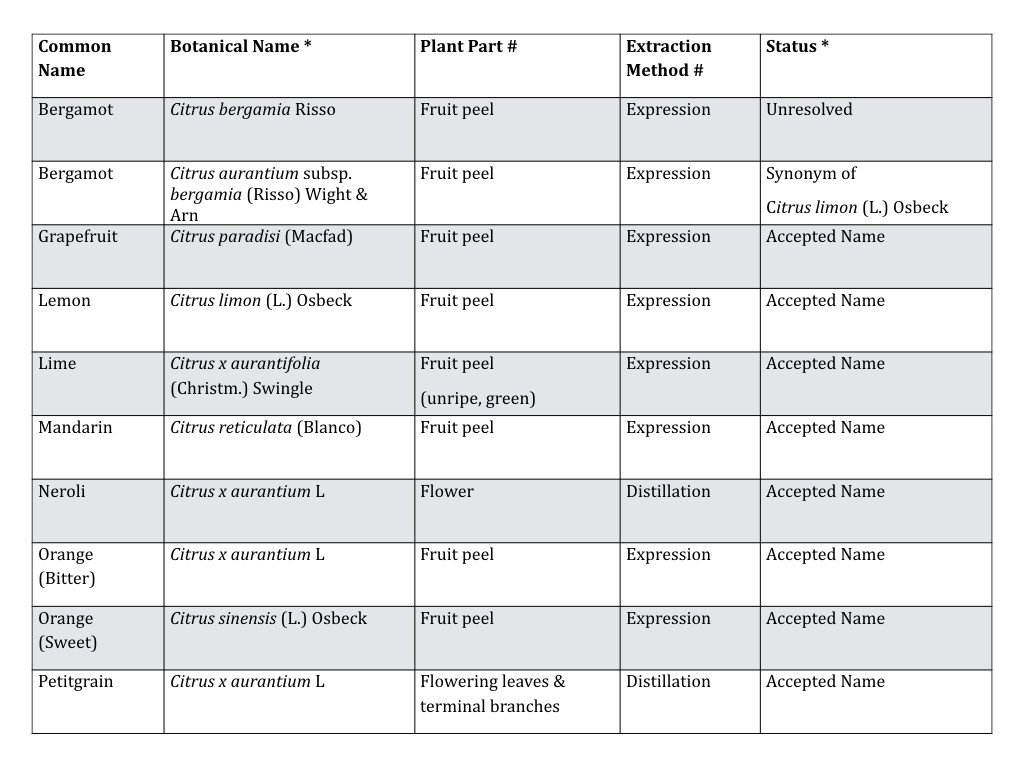

Citrus peel essential oils are some of the most popular and widely used essential oils. Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) peel oil is produced in greater quantity than any other essential oil, although a large part of the production is used by the food flavouring industry (Tisserand, R. & Young, R. 2014). Citrus oils are also widely used in perfumery as top notes to provide freshness and lift. Many other citrus peel oils are used in aromatherapy, including Lemon (Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck), Bitter Orange (Citrus x aurantium L) and Bergamot essential oils.

Bergamot itself is very popular and it is the characteristic aroma of Earl Grey tea. In addition to its use in aromatherapy, Bergamot oil is used in a wide range of commercial products, including fragrances. The name “Bergamot” is derived from the city of Bergamo in the north of Italy (Lawless, J. 2014), the country that produces the majority of the world supply of Bergamot essential oil (Citrus Variety Collection, n.d). The fruits are often considered to be inedible (they taste of “perfume”) however the plant is grown on a small scale in Mauritius where Bergamot fruit juice is consumed by the locals (Encyclopedia of Life, n.d). (Encyclopedia of Life, n.d).

The importance of binomials

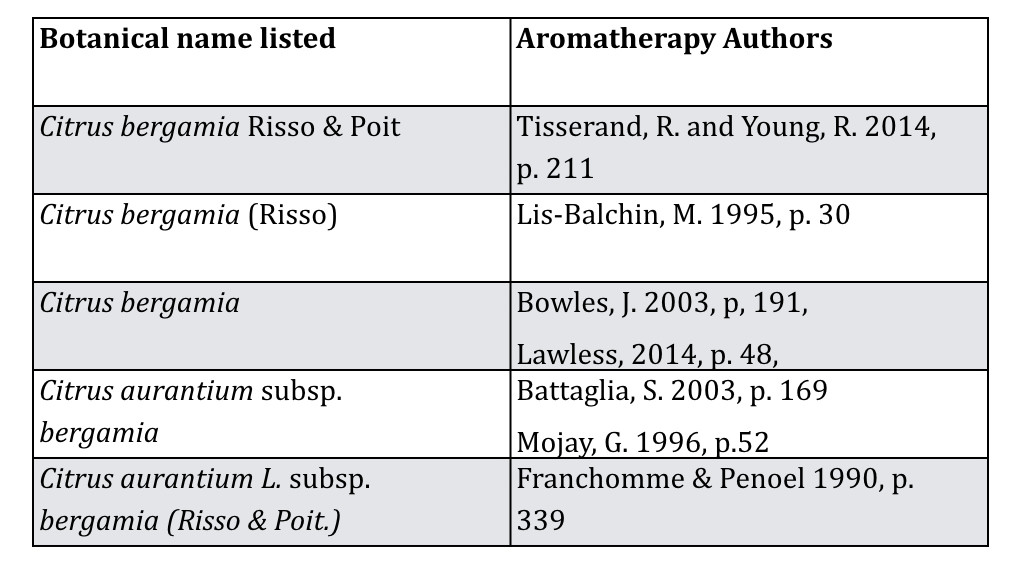

Since the binomials of plants are used to correctly identify essential oils, any changes to binomials affect the industries that use essential oils. A review of aromatherapy literature shows that different authors list different botanical names for Bergamot oil (Table 1).

The International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) 1998 standard for bergamot oil (ISO 3520:1998) is Oil of Bergamot Italian type. This standard was last reviewed and confirmed in 2015 (International Organisation for Standardisation, (ISO), 2015).

There are several organisations that provide taxonomy databases listing the binomials for plant species, including: The Plant List, Tropicos.org, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), the National Plant Germplasm System (US) and the PLANTS Database (United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service. See Appendix A for information about the botanical databases listed above, including links to these invaluable botanical resources.

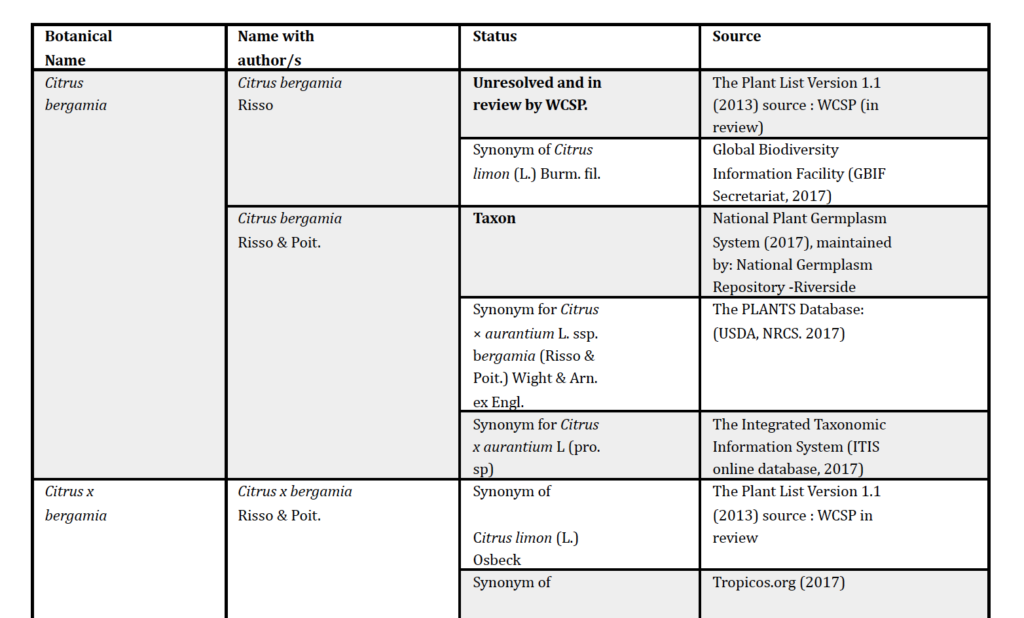

To further investigate the correct botanical name for Bergamot oil, a variety of international botanical databases were reviewed. This revealed conflicting reports (Table 2) and several names were used more than once. Many names that are commonly used for Bergamot are listed as synonyms. A synonym is a name previously used for a species but not the name but not current name (The Plant List, 2013).

Table 2: Review of the status scientific names for ‘Bergamot’ from botanical databases. Click on the image for full table.

Some of the names clearly refer to Bergamot oil (such as Citrus aurantium subs. bergamia or Citrus bergamota). However some would create confusion if they were adopted universally, such as Citrus limon (or Citrus x limon) which is a binomial currently associated with Lemon oil. However, Bergamot is not a solitary case among citruses. The taxonomy of this plant genus has been almost as varied as the species and varieties included. There are several hundred different citruses known, and most of them are of unknown origin. Not all of them are used for essential oil production, and Table 4 shows those most commonly used for essential oil production.

Taxonomy – how did we get here?

Taxonomy is the science of naming, describing and classifying living organisms, which includes all known plants, animals and microorganisms. Taxonomists use morphological, behavioural, genetic and biochemical observations, to identify, describe and arrange species into classifications, which also helps them put all newly discovered new organisms into the existing system. (Secretariat of Convention on Biological Diversity (2007).

All living species are arranged according to their evolutionary relationships into a hierarchical system called biological classification. The levels of classification are Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species. Higher levels of classification are more distantly related (Encyclopaedia of Life, n.d.). Plants and animals are both included in the domain Eukaryota (Keeling et al, n.d.) and plants belong to the Kingdom Plantae. (Weisz, n.d.). A taxon (plural taxa) is a unit of any rank (i.e. kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species) referring to an organism or group of organisms (Business Biodiversity and Offsets Programme 2012).

Botanical Nomenclature

The scientific naming of plants is called botanical nomenclature (Royal Botanic Gardens, Victoria, n.d). The current rules of naming plants are outlined in Division III of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants (ICN). Changes to the ICN are debated and decided by hundreds of international specialists at the International Botanical Congress, which is held every six years (Funk, Herendeen & Knapp, 2017).

The system of binominal nomenclature (identifying plant species by a set of two names) was established by Carl Linnaeus in his book Species Plantarum in 1753 (Natural History Museum, n.d.). The binomial is written in Latin and consists of the genus followed by the species. The first letter of the genus is capitalized, and both genus and species are written in italics or underlined. The plant species may also have further classifications such as a subspecies or variety. If a plant is a hybrid (a cross between two separate species) the botanical name may also include an x between the genus and species. Examples can be seen in Table 2.

The name/s of those who originally described the plant in a published book or journal (author/s) are generally cited after the botanical name. In some cases the author’s name may be abbreviated, or it may include the opinion of a later author on the status of the original botanical name, written after the authors name and not enclosed in brackets (Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, 2012). For example, Citrus aurantium var. bergamia (Risso) Brandis.

In the early years of taxonomy, plants were often classified according to their physical appearance (morphology) or their geographical location. Hence we have names like Lavandula angustifolia (narrow-leaved lavender), Melaleuca alternifolia (melaleuca with alternating leaves), Rosa damascena (rose from Damascus) or Cedrus atlantica (Cedar from the Atlas mountains). In recent years genetic research has enabled scientists to study the DNA of plants to better understand their evolutionary and familial relationships (Chase & Fay 2001)

Taxonomy is our only tool for correct identification of individual species. From gardening to essential oil research, from herbal medicine to discovering new species, the ability to identify a plant is crucial.

Note: The history of taxonomy is beautifully told in Beyond the Gardens: The Plant Family Tree, Created by Lonely Leap (2013) and commissioned by Royal Botanical Gardens Kew: Narrated by Mark Chase, Keeper of the Jodrell Laboratory. http://www.richannel.org/collections/2013/kew-gardens#/beyond-the-gardens–the-plant-family-tree This documentary explores the journey of scientists classifying plants from the early origins of taxonomy in the 18th century to the genetic research of the 21st century.

The Citrus genus: an open question

Now that we know where taxonomy began and how important it is for aromatherapy, let’s look at the situation with citruses, because this where things get a little complicated. Many researchers have identified and named species from the Citrus genus. This has resulted in many synonyms for individual plant species and confusion regarding the correct binomial of some species.

Now that we know where taxonomy began and how important it is for aromatherapy, let’s look at the situation with citruses, because this where things get a little complicated. Many researchers have identified and named species from the Citrus genus. This has resulted in many synonyms for individual plant species and confusion regarding the correct binomial of some species.

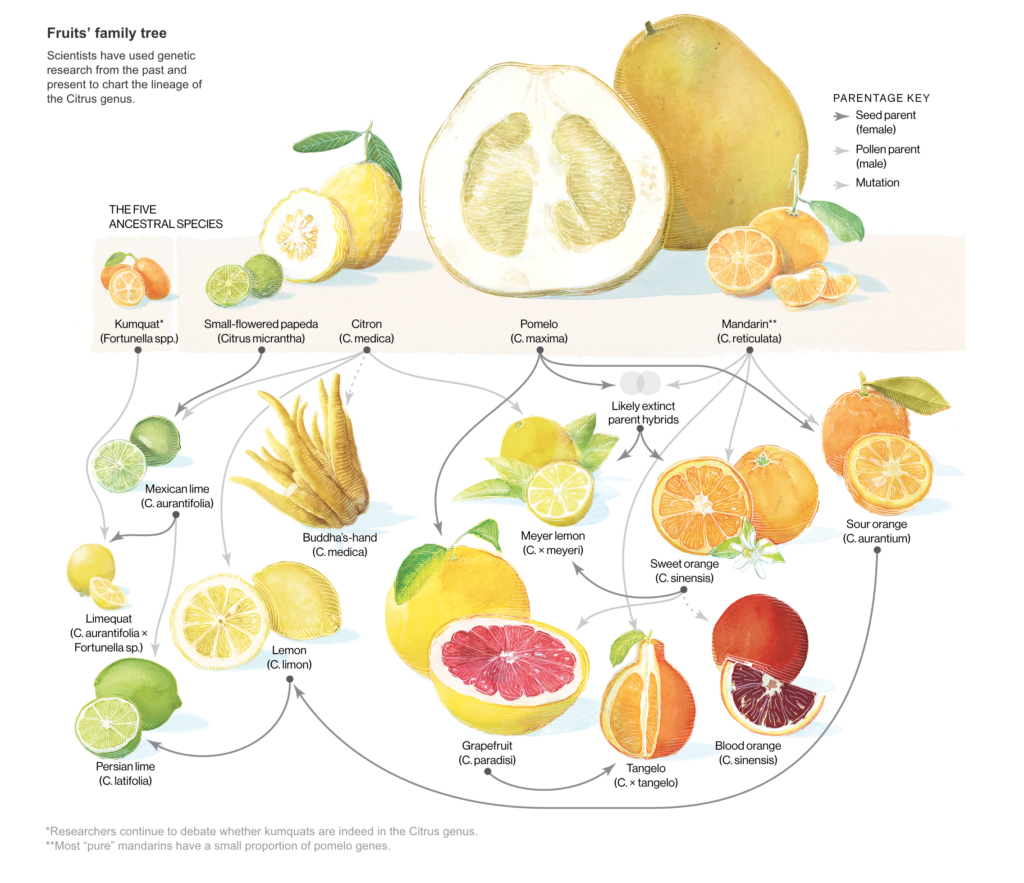

Most Citrus trees are hybrids from only a few ancestral plant species. Genetic research is providing new insights into the origins of Citrus species. According to Curk et al (2014) the most economically important Citrus species originated from four ancestral taxa (Mandarin: Citrus reticulata, Pummelo: Citrus maxima, Citron: Citrus medica and Papeda: Citrus micrantha). This theory is widely accepted. However, an additional fifth ancestral species (Kumquat: Citrus japonica) is also identified by some researchers (Ramadugu et al, 2015).

Naming of the Citrus species

The two main classification systems for the Citrus genus are: Swingle (Walter T. Swingle, USA, 1943) and Tanaka (Tyosaburo Tanaka, Japan). Swingle identified only 10 species of the subgenera Citrus and many subspecies and varieties whilst Tanaka gave species status to many of the plants listed as subspecies by Swingle (Krezdorn, n.d.). For example Bergamot was classified as a separate species (Citrus bergamia) by Tanaka (Curk et al, 2014) and as a subspecies of sour (bitter) orange by Swingle (Krezdorn, n.d.). Swingle’s system is more widely accepted. In many cases the botanical names listed by Swingle and Tanaka were first published by previous scientists, as is the case of Citrus bergamia (Risso), which was first published in 1826 (The Plant List, 2013).

To investigate the current accepted scientific name for plants producing the most commonly used Citrus essential oils I reviewed The Plant List (2013). The results are listed in Table 4. The plant part and extraction methods for each of the essential oils listed by Tisserand and Young (2014) is also included.

Table 4: Botanical names, plant parts and extraction methods of common Citrus essential oils * The Plant List (2013) # Tisserand & Young (2014)

The Plant List is an international collaboration that provides information on the accepted scientific name for selected plant species. The Plant list assigns each plant name listed with a status, either accepted, synonym or unresolved. An accepted name is the name that they consider should be used for a species (or subspecies, variety or forma). A synonym is a name that has previously been used for a species, but is not the current accepted name. An unresolved name is a plant name that it is not yet possible to assign as either an accepted name or a synonym. (The Plant List, 2013).

Why does it matter?

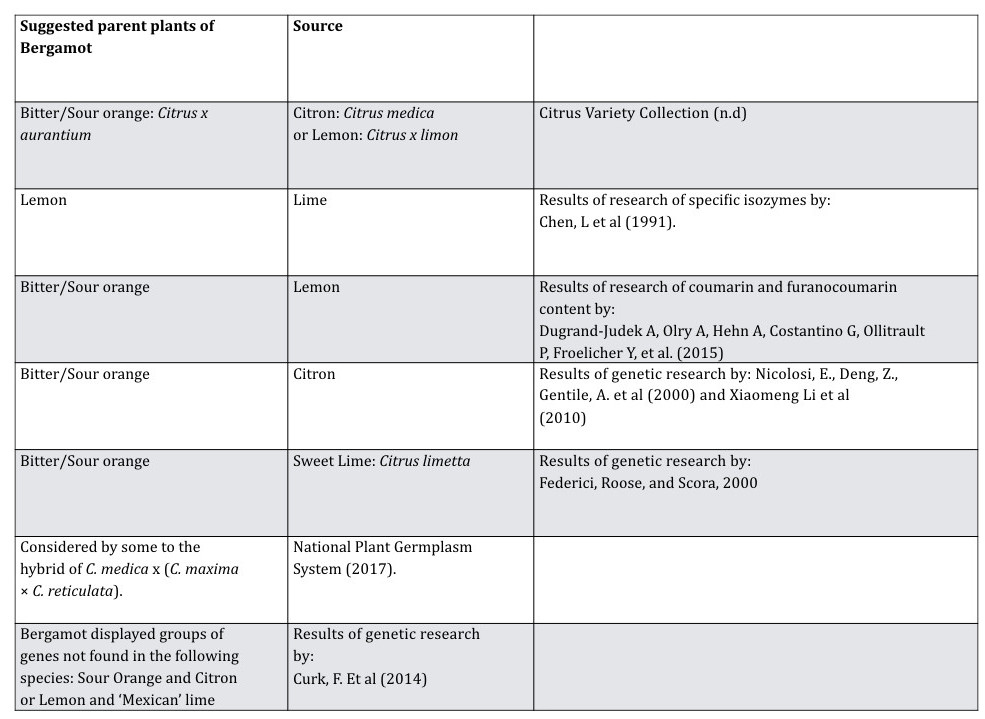

Let’s go back to Bergamot. We have seen and demonstrated that this plant may, surprisingly, have a less confusing common name than the binomial name assigned to it by taxonomists. This is partially because of the unclear origins of the plant. Whilst experts agree that Bergamot is a hybrid, there is no consensus on its parent plants, and this has an impact on the accepted binomial. Several studies have investigated the genealogy of Bergamot, sometime producing conflicting results.

The Plant List (2013) classifies the botanical name Citrus bergamia Risso as ‘unresolved’ and in review by WCSP. In the botanical literature reviewed, the following scientific names were considered an accepted name by at least one resource:

- Citrus bergamia Risso & Poit. by the National Plant Germplasm System (2017),

- Citrus × aurantium ssp. bergamia (Risso & Poit.) Wight & Arn. ex Engl. by the PLANTS Database: (USDA, NRCS. 2017),

- Citrus x aurantium L (pro.sp) by the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS online database, 2017)

- Citrus x limon (L.) Osbeck by Tropicos.org (2017),

- Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck by The Plant List (2013),

- Citrus limon (L.) Burm. fil. by the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF Secretariat, 2017).

Some of these names would work for aromatherapy, as Bergamot would have a different binomial to other citrus peel essential oils, and the name includes ‘bergamia’ in either the species or subspecies. However if taxonomists decided that the accepted botanical name of Bergamot is either Citrus limon or Citrus x aurantium this could cause confusion for businesses and individuals that use Bergamot, Bitter Orange and/or Lemon essential oils.

The constituents of these three essential oils are different, and hence their therapeutic guidelines and safety considerations also differ. Bergamot expressed is more phototoxic than Bitter Orange, which in turn is more phototoxic than Lemon expressed. In addition, both Lemon expressed and Bitter orange expressed are potentially more skin sensitising than Bergamot expressed (Tisserand and Young 2014). Therefore it is important for safety reasons to clearly differentiate between these three essential oils.

Conclusion

It is unfortunate that this taxonomic confusion exists in the class of essential oils where misidentification could have unfortunate safety consequences.

Governments and other regulatory bodies provide guidelines for labelling essential oils and products containing them. Businesses that manufacture, distribute and sell such products have to find a way to comply with those regulations, while still clearly and unequivocally identifying the correct essential oil. It is important that the Aromatherapy industry and other industries using essential oils are aware that there is no consensus among taxonomists for the correct botanical name for Bergamot.

It would be in everyone’s interest to find a correct and clear identifier for all citruses. . For now, the aromatherapy industry must make sure to clearly identify essential oils as it is vital to safety and comply with current regulations. If regulations change in the future, the industry will need to find a way to both comply with new regulations and assure minimal risk.

Please note that the information in this article is provided for general information purposes only. It is not a legal authority for statutory or regulatory purposes.

References

Australia’s Virtual Herbarium (2012). Plant names – a basic introduction, Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, Australian National Botanic Gardens.

http://www.anbg.gov.au/chah/avh/help/names/

Battaglia, S. (2003).The complete guide to aromatherapy, second edition. Brisbane: The International Centre of Holistic Aromatherapy.

Bowles, E. J. (2003). The chemistry of aromatherapeutic oils, 3rd edition. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin.

Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme (BBOP) (2012). Glossary. BBOP, 2nd updated edition, Washington, D.C, Forest Trends.

http://www.forest-trends.org/documents/files/doc_3100.pdf

Chase, M. & Fay, M.F. (2001) Ancient flowering plants: DNA sequences and angiosperm classification. Genome Biology 2(4): reviews1012.1-1012.4

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC138926/pdf/gb-2001-2-4-reviews1012.pdf Accessed 27th October, 2017]

Chen, L. et al (1991) A study on the taxonomy of citrus with GOT isozymes, (Abstract), Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 1991-01

http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-YYXB199101005.htm

Citrus Variety Collection (n.d.) Bergamot sour orange hybrid, College of Natural and Agricultural sciences, University of California Riverside, http://www.citrusvariety.ucr.edu

Curk, F. et al (2014).Next generation haplotyping to decipher nuclear genomic interspecific admixture in Citrus species: analysis of chromosome 2, BMC Genetics201415:152, http://bmcgenet.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12863-014-0152-1

Dave’s Garden (2017). Searching Botanary, https://davesgarden.com/guides/botanary/ Accessed 28th October, 2017.

Dugrand-Judek A, Olry A, Hehn A, Costantino G, Ollitrault P, Froelicher Y, et al. (2015) The Distribution of Coumarins and Furanocoumarins in Citrus Species Closely Matches Citrus Phylogeny and Reflects the Organization of Biosynthetic Pathways. PLoS ONE 10(11): e0142757. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142757 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4641707/pdf/pone.0142757.pdf

Encyclopedia of Life (n.d.), http://eol.org/

Federici, C.T., Roose, M.L. and Scora, R.W. (2000). RFLP analysis of the origin of Citrus bergamia, Citrus jambhiri, and Citrus limonia. Acta Hortic. 535, 55-64.

https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2000.535.6

Franchomme, P. & Penoel, D. (1990), L’aromatherapie exatement: Encyclopédie de l’utilisation thérapeutique des huiles essentielles, (French), France: Roger Jollois.

Funk, V.A, Herendeen, P & Knapp, S. (2017). Taxonomy: naming algae, fungi, plants, Nature: International weekly journal of science, Macmillan Publishers Limited, Springer Nature. https://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v546/n7660/full/546599c.html

GBIF Secretariat (2017). Citrus limon (L.) Burm. fil. GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist Dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei https://www.gbif.org/species/9198046

GBIF.org (2017) What is GBIF? Global Biodiversity Information facility, Copenhagen. : http://www.gbif.org/

Germplasm Resources Information Network (2015) Welcome, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville (MD). http://www.ars-grin.gov/

Germplasm Resources Information Network (2017) National Plant Germplasm System, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville (MD). http://www.ars-grin.gov/npgs/index.html

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) online database (2017) ITIS Report Citrus x aurantium , http://www.itis.gov

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2015). ISO 3520:1998, Oil of bergamot , Italian type, International Organisation for Standardisation, Geneva. https://www.iso.org/standard/8893.html

Keeling, P. Simpson, A. Leander, B.S (n.d.). Eukaryota, Encyclopaedia of Life. http://eol.org/pages/2908256/overview

Krezdorn, A.H, n.d. Classification of Citrus, Department of Fruit Crops, University of Florida. https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/hort_403/readings/Reading_32.pdf

Lawless, J. (2014). The encyclopedia of essential oils: The complete guide to the use of aromatic oils in aromatherapy, herbalism, health and well-being. UK: Harper Torsons.

Lis-Balchin, M. (1995). The chemistry and bioactivity of essentil oils. Great Britain: Aberwood Publishing Ltd.

Lonely Leap (2012). Beyond the Gardens: The Plant Family Tree. http://www.richannel.org/collections/2013/kew-gardens#/beyond-the-gardens–the-plant-family-tree

Missouri Botanical Garden (2010) The Plant List (video), from: http://www.mobot.org/theplantlist/

Missouri Botanical Garden (n.d.) Troipicos. http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/media/fact-pages/tropicos.aspx

Mojay, G. (1996). Aromatherapy for Healing the spirit. London: Gaia Books Limited.

National Plant Germplasm System (2017) Citrus bergamia. Risso & Poit. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?10698

Natural History Museum (n.d), Linnaeus and Hortus Cliffortianus, http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/scientific-resources/collections/botanical-collections/clifford-herbarium/linnaeus-and-hortus-cliffortianus/index.html

Nicolosi, E., Deng, Z., Gentile, A. et al (2000). Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers (Abstract), Theor Appl Genet (2000) 100: 1155. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s001220051419

Price, S. &. Price. L. (2012). Aromatherapy for health professionals, fourth edition. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Ramadugu, C. et al (2015) Genetic analysis of citron (Citrus medica L.) using simple sequence repeats and single nucleotide polymorphisms, Scientia Horticulturae 195 (2015) 124–137, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304423815301692

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (n.d). https://www.kew.org/

Royal Botanic Gardens, Victoria, (n.d),Botanical nomenclature, https://www.rbg.vic.gov.au/science/herbarium-and-resources/national-herbarium-of-victoria/botanical_nomenclature

Secretariat of Convention on Biological Diversity (2007). Guide to the Global Taxonomy Initiative, CBD Technical Series, Convention on Biological Diversity https://www.cbd.int/doc/programmes/cro-cut/gti/gti-guide-en.pdf

The Plant List (2013). Version 1.1 http://www.theplantlist.org/

Tisserand, R. &. Young, R.(2014). Essential Oil Safety: A guide to health care professionals. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Tropicos.org (2017). Missouri Botanical Garden. http://www.tropicos.org

USDA, NRCS. (2017). The PLANTS Database, http://plants.usda.gov

Weisz, N. (n.d.). Plantae, The Encyclopaedia of Life, : http://eol.org/pages/281/overview

WCSP (2017). World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. : http://apps.kew.org/wcsp/

Xiaomeng Li et al (2010). The origin of cultivated Citrus as inferred from Internal Transcribed Spacer and Chloroplast DNA Sequence and Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Fingerprints. J. AMER. SOC. HORT. SCI, 135(4), p. 341–350. http://journal.ashspublications.org/content/135/4/341.full.pdf

Appendix: International botanical databases reviewed:

The Plant List:

The Plant List is a collaboration between the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (UK) (please include link imbedded in heading) https://www.kew.org/ and the Missouri Botanical Garden (USA) (please include imbedded link) http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org and other contributors (The Plant List, 2013).

The Plant List (Version 1.1) contains a list of the current accepted scientific names for the following major plant groups: Angiosperms (flowering plants), Gymnosperms (including conifers), Pteridophytes (such as ferns) and Bryophytes (including mosses). It also provides information on synonyms and unresolved plant names. The Plant List contains data from the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, including unpublished data that is still being compiled, or has been completed and is awaiting review by experts (The Plant List, 2013).

World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

The World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP) was developed by the Royal Botanical Gardens Kew (Missouri Botanical Garden, 2010) and is a collaborative program between different botanical experts. It is peer reviewed and provides information on the accepted botanical names and synonyms of selected plant families. The WCSP has 155 contributors from 22 countries (WCSP, 2017). The Citrus genus is currently not listed on the WCSP public database. However the WCSP does publish world checklists of the following essential oil producing plant families: Myrtaceae and Conifers which can be purchased via the Kew Gardens website. (please include imbedded link) http://shop.kew.org/catalogsearch/result/?q=world+checklist

Tropicos.org

The Missouri Botanical Gardens has an online data base of botanical species called Tropicos (Missouri Botanical Garden, n.d). Tropicos was originally created for research purposes within the Missouri Botanical Garden but has since been made available to the scientific community worldwide (Tropicos.org, 2017).

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS)

The ITIS is a partnership between US, Canadian and Mexican agencies (ITIS- North America) and other organisations including the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (The Integrated Taxonomic Information System, 2017)

Global Biodiversity Information Facility

The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) is the largest biodiversity database on the internet. It includes links to hundreds of millions of records shared by hundreds of institutions worldwide. The GBIF was set up by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (GBIF.org, 2017). Records can be searched according to location, helping researchers to find local records.

US National Plant Germplasm System

The U.S. National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) is a partnership between public and private sectors. The NPGS is managed by the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), which is the internal research agency of the United States Department of Agriculture (Germplasm Resources Information Network, 2017).

‘It is the NGRP’s responsibility to: acquire, characterize, preserve, document, and distribute to scientists, germplasm of all lifeforms important for food and agricultural production’ (Germplasm Resources Information Network, 2015).

The PLANTS Database:

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) provides the PLANTS Database which gives standardized information about various plants (including vascular plants)of the U.S. and its territories. (USDA, NRCS. 2017).

0 Comments