Welcome to the world of essential oils! If you’re here, you’ve probably been recently introduced to essential oils and are looking to learn all you can. This is the first of a series of posts intended for essential oil beginners, or anyone who’s been using essential oils but wants to gain a more solid understanding of the basics. To start, let’s talk about what an essential oil is and how it works.

The definition of ‘essential oil’

Merriam Webster says: “any of a class of volatile oils that give plants their characteristic odors and are used especially in perfumes and flavorings, and for aromatherapy”. Where “volatile” means: “(of a substance) easily evaporated at normal temperatures”. What this means is that an essential oil is made up of the distilled parts of a plant that are volatile. A typical essential oil consists of 100 or more chemical constituents, each one created by the plant.

It’s important to note that you need to process many plants to create one bottle of essential oil, and thus essential oils are very concentrated. To better illustrate what exactly an essential oil is, let’s look at how they’re made.

The making of an essential oil

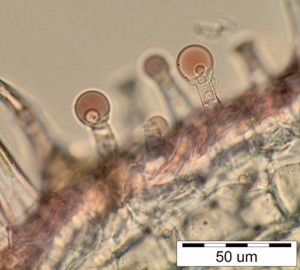

The constituents of an essential oil are created by specialized plant cells, which secrete them into very tiny sacs or glands, either on the surface of a leaf or flower, or deeper inside the plant tissue. Most essential oils are extracted using one of two methods: mechanical expression, which is only used for citrus fruits, and distillation. The aim of distillation – or expression – is to cause the glands containing the essential oils to release their contents.

– Mechanical expression

This method is used for extracting essential oils from the rinds of citrus fruits. The whole fruits are tossed around in a large drum mechanical device while being scarified or rasped by thousands of tiny spikes. These pierce the essential oil glands that dot the surface of the fruit, and this extracts the essential oil in a cold process (note that this is not ‘cold pressing’, a process used to extract vegetable oils from nuts or seeds). Water is used to flush the essential oil away from the fruit, and a centrifugal separator then separates the essential oil from the water and any fruit juice. The process can be seen here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCcBNrvyU5s&t=97s and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ob5Vo2e4yP8

Today it is highly mechanized, but historically expression was done by pressing the inverted fruit peel against a spikey ball suspended over a bucket or barrel. Expression is generally preferred, as it produces an essential oil with a superior odor compared to distillation. Essential oils extracted this way sometimes contain non-volatile components such as furanocoumarins, which are the molecules responsible for the phototoxicity of citrus oils. Distilled citrus fruit oils are widely used in the food industry, where taste is more important than odor, or in order to avoid the risks associated with phototoxicity. More on citrus oils here: https://tisserandinstitute.org/learn-more/citruses-a-comparison-of-different-oils/

– Distillation

This method makes use of water and heat to achieve separation of the essential oil from the plant material. During hydrodistillation (the method that has been in use for about 1,000 years), plant matter is boiled in water, and the water vapor plus volatile essential oil components are condensed back into liquid form through cooling. Since essential oils float on water, separation is straightforward. A more modern form of distillation, steam distillation, uses either ‘dry’ or ‘wet’ pressurized steam to cause evaporation of the volatile components. (Wet steam contains tiny water droplets, while dry steam does not.) During this process, plant matter is placed in a closed chamber and steam is passed through it, which again causes the volatile compounds in the plant to evaporate. In the final step, as in hydrodistillation, the water and essential oil are condensed and then separated, leaving just the pure essential oil. Lavender is an example of an oil that is steam distilled https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h-vlvvzVa10

There is a third type of distillation, known as “dry distillation” and it has been used in North Africa for as long as hydrodistillation. It entails heating the plant material – usually leaves, wood or twigs – simply by heating the still, but with no water or steam involved. The vapors are then collected. This is more like burning, and can cause the formation of carcinogenic compounds, so dry distilled oils are not much used today in aromatherapy. More here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dry_distillation

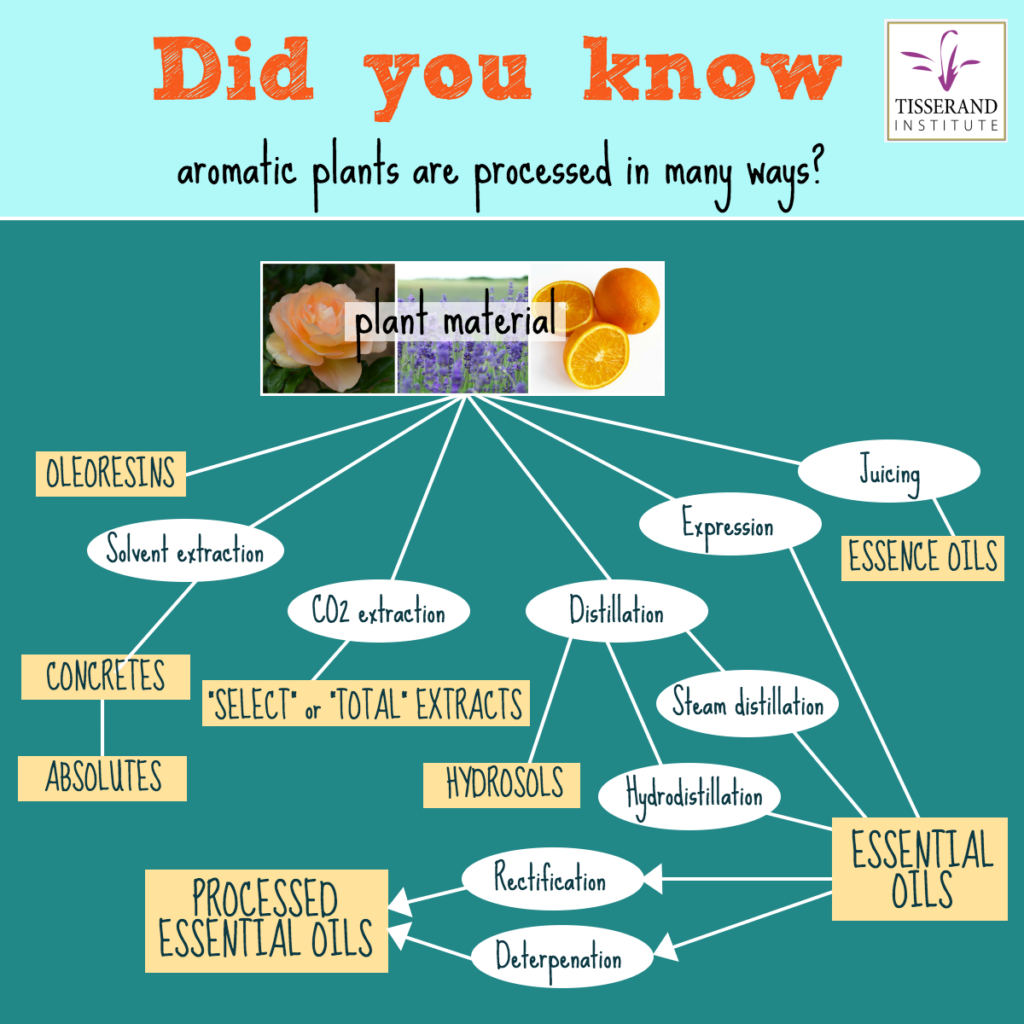

Other aromatic extracts

In addition to essential oils, there are various other aromatic plant extracts that are sometimes used in aromatherapy.

– Absolutes

Absolutes are produced by solvent extraction, and while this method produces something similar to an essential oil, it is by definition not truly an essential oil. This method uses a solvent to dissolve out aromatic molecules, thus separating them from the plant matter. The mixture then goes through a two-stage process that separates the absolute from the solvent. The first step produces what is called a concrete. As the name suggests, concretes are solid at room temperature, and this is because they contain plant waxes. In the second step of the process the waxes are separated out, leaving the absolute. Absolutes used to be made on a commercial scale by a process called ‘enfleurage’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7U-ktfOqVz0 but this is no longer used commercially.

Jasminum grandiflorum flowers

One difference between an essential oil and an absolute, is that absolutes contain a predominance of heavier, non-volatile molecules, and because of this they are more viscous than essential oils. Solvent extraction is often used for plants that are too delicate for steam distillation, such as Jasmine flowers. The most common solvent is hexane, and a few parts per million of hexane do remain in the final extract. While this is by no means toxic, absolutes are sometimes avoided because they are processed using a synthetic solvent.

– CO2 extracts

CO2 extraction is a relatively new method, and like solvent extraction it does not produce a true essential oil. In fact it is a type of solvent extraction, but this time the solvent is carbon dioxide, which takes on the properties of a solvent with certain combinations of temperature and pressure. The product of this process is aptly named a CO2 extract, and while it is similar to an essential oil it contains more than just the volatile constituents. You could think of CO2 extracts as having both the lighter molecules of an essential oil and also the heavier molecules of an absolute. CO2 extracts tend to smell more like the living plant than essential oils, and have uses in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and aromatherapy. Since we are constantly inhaling CO2 from air, even if traces remain in the extract, this is not a concern. More on CO2 extracts here: https://tisserandinstitute.org/learn-more/co2-extracts-spotlight/

– Resinoids and oleoresins

Both resinoids and oleoresins contain resinous – often solid – compounds, so many of them are extremely viscous, resinoids often being virtually solid. Resinoids are made by solvent extraction in a similar way to absolutes, and are mostly used in perfumery. They are soluble in alcohol, but not fatty oils or essential oils, so they have little use in aromatherapy. Benzoin is an example of a resinoid. Oleoresins are produced for the food and pharmaceutical industries, and as the name suggests, they contain both essential oil and resin. Most are only soluble in water, not oil or essential oils. However, one oleoresin, Copiaba, does mix with other essential oils. More on Copaiba here https://tisserandinstitute.org/learn-more/copaiba-oil/

– Hydrosols

Hydrosols, also known as hydrolats, are approximately 99.95% water. Like essential oils they are produced using distillation. When the water and essential oil separate, the water also carries a very low concentration of aromatic molecules – especially the ones with greater water solubility. Because the concentration of aromatic molecules is so low, they do not separate, but remain dissolved in the water. Hydrosols are often used for baths, for gargling, and for children’s ailments. More on hydrosols here https://phytovolatilome.com/hydrolats-demystifying-mystical-waters/

Vegetable oils

As a final note about what exactly essential oils are made of, I’ll talk about what makes essential oils different from vegetable (fatty) oils. Vegetable oils are also extracted from plants, such as olive oil, coconut oil, sunflower oil, etc. These oils are recommended for diluting essential oils (often called carrier oils in this context), and they even both have ‘oil’ in their name. However, vegetable oils are different from essential oils in one very important way: vegetable oils are composed mainly of non-volatile molecules called triglycerides (composed of three fatty acids plus glycerol) whereas essential oils consist mainly of much smaller, volatile compounds. Triglycerides are relatively large molecules, much too heavy to carry over during distillation – and, they are virtually odorless. Some vegetable oils do carry distinct odors, but this is due to other compounds.

This distinction is critical, because some people expect essential oils to behave like traditional vegetable oils in terms of making mixtures, even though they are composed of completely different types of compounds. Plainly put, vegetable oils are fatty (greasy), and essential oils are not. Some people like to use the stain test to determine the difference. Vegetable oils will leave an oily residue or stain on a fabric or tissue, whereas essential oils will evaporate without leaving a stain. Well, most of them will, but blue Chamomile oil for example can leave a blue stain!

Go here to read Part 2 of the Beginner’s Guide.

Beautiful. Thank you.

Gracias por Compartir tan interesante información. un abrazo desde Aceites esenciales, bienestar y salud.alicante

Thank you!

Wow, thank you for the exciting summary on oils.