by Tamara Agnew PhD

The current mood around aromatherapy is complex. There are companies and company representatives making ludicrous health claims which are damaging to the reputation and therefore the development of the practice. In contrast, there are the vocal cynics and critics who, using mostly offensive, ignorant language, insinuate that all complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practice is sham, there is no evidence that it works (a very broad statement), those who practice it are quacks, and those who research it are pseudoscientists. Finally, there are practitioners who strongly support research, and then there are those who don’t. In between, some agree a little, but they do not necessarily trust the intentions of the people who conduct the research. This is the climate we are all operating in. For some, none of this may matter, but for me it is a personal challenge!

I have an accredited aromatherapy qualification earned at Edinburgh Napier University in a complementary medicine program that was later shut down following a relentless campaign by critics in the UK to target all CAM university programs. I have a PhD following my investigation into how essential oils impact the physical and psychosocial symptoms of acne vulgaris (Agnew et al., 2014). These days I am less clinician, more clinical and social scientist. My kind of research looks at how an intervention impacts different outcomes in specific populations. Having not worked as a clinician for a number of years, I am no longer expert in the nuances of clinical practice, but I do have a sound understanding of the philosophical and theoretical perspectives underpinning aromatherapy, and a solid knowledge of essential oils, and holistic practice. For me, the opportunity to conduct research means that ultimately more people can have access to the healing effects of essential oils. The only way to make that a reality is to prove that it works.

This blog post argues that rigorous research evidence is the way forward if we want to build a solid, respected professional health option for all consumers. It describes evidence-based practice; outlines anecdotal evidence – both the positives and the negatives; provides a statement about why we need more clinical evidence and concludes by defining what an evidence-based practice can mean for the practitioner.

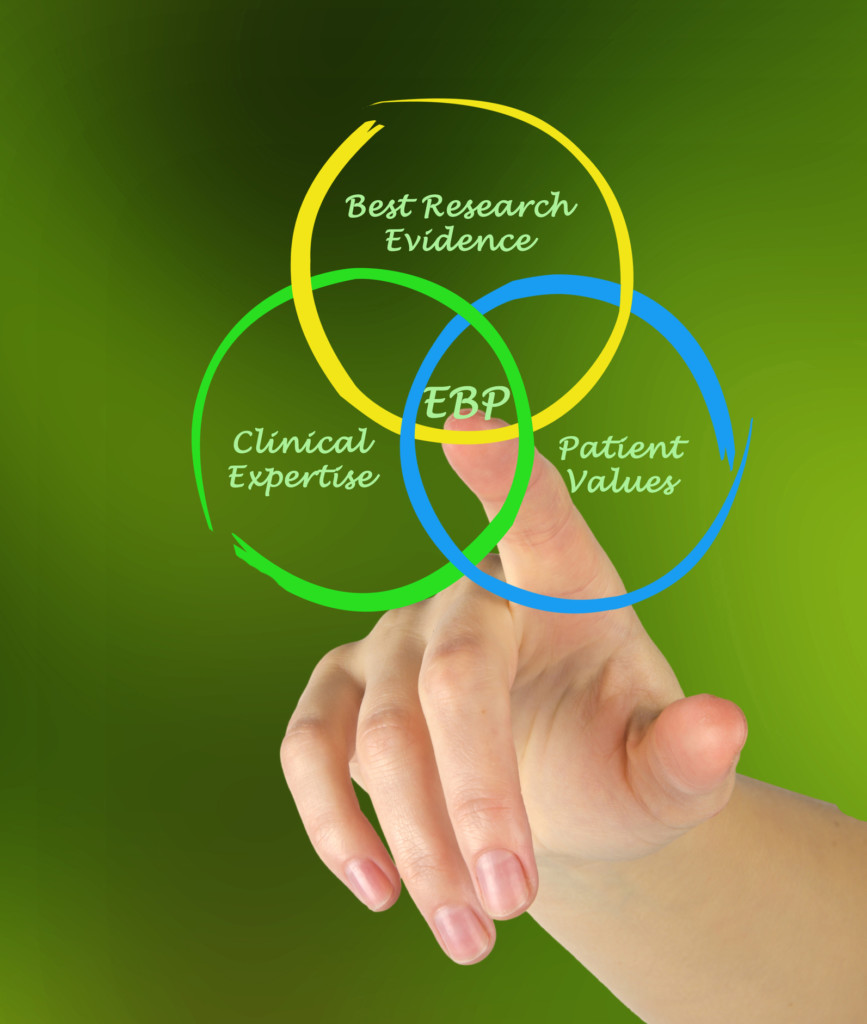

Evidence-based practice (EBP)

EBP “requires that decisions about health care are based on the best available, current, valid and relevant evidence. These decisions should be made by those receiving care, informed by the tacit and explicit knowledge of those providing care, within the context of available resources” (Dawes et al., 2005). The EBP framework is a restructure of the clinical experience from the dominant “expert” knowledge, to treatment based on the needs of the patient, combined with learned clinical skills and current best evidence. Early critics of this model resisted the science, favouring instead intuition and the “incommunicable knowledge” of the art of medicine (Bradley, 2012).

Today, the model is largely accepted as beneficial in medical practice, however the emphasis on the needs of the patient are often lost in bureaucracy. In theory, EBP is a perfect fit for CAM practice. The needs of the client have always been at the very centre of holistic practice; skills and theoretical reasoning gained through training and qualifications support the practice, however, evidence is still mostly anecdotal. This is largely because of the limited evidence base (Fischer et al., 2014), but also the value the clinician places on their own experience. Experience is not underestimated, but it is not evidence.

The EBP model should become the norm. Sometimes, there are risks associated with clinical decision making, and society generally is becoming more litigious when something goes wrong. Further, because the client pays through out-of-pocket expense for the provision of an aromatherapy treatment, failure to provide evidence of the effectiveness of, or justification for the treatment may be perceived as a con. Both of these outcomes are potentially very damaging to the reputation of the practitioner and aromatherapy.

The problem with relying on anecdotal evidence

“Anecdotal evidence” is a favorite amongst practitioners. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary (2019) anecdotal evidence is “evidence in the form of short stories that people tell about what happened to them”; it is a summary of your clinical experience. In order to be published, anecdote must be written as a case study or case series, and these clinical experiences have an important place in our collective understanding of practice. However, in terms of evidence, a published case study is the lowest form of human research evidence in the hierarchy.

Hierarchy of evidence

Anecdote provides a strong narrative that people can relate to, and this makes it difficult to set aside when we are thinking about evidence for practice. Often, anecdotal evidence is the starting point to much larger research studies and so it is not completely discounted, and it is why it does make an appearance in the hierarchy of evidence. However, the case study is not enough evidence on which to base clinical decision making.

Think about it like this – you might hear someone say, “my grandmother died at the age of 96, with a cigarette in her hand; she didn’t die of cancer”. Does this one experience suggest that there is no link between smoking and lung cancer? Even if you heard this half a dozen times throughout your life, from different people, would you be encouraged to go and pick up a cigarette? Probably not, because these individual stories are just that, unique experiences. Hard evidence, whilst often very dry and sometimes difficult to comprehend, tells us a very different story.

There are a number of terms we use in clinical research that help to identify why anecdote is not the most reliable form of evidence. For example, we talk about regression to the mean –that everything will even out over time, with or without intervention (Barnett et al., 2004). For example, we might apply an essential oil to treat someone experiencing cold symptoms. It is difficult to say that this person was “cured” based on the treatment, because the cold symptoms would have naturally resolved with time. It may even be difficult to claim that treatment alleviated some of the symptoms, because the client may not have reported using cold medicine or other forms of cold remedy.

In research, bias means “a deviation from the truth” (Simundić, 2013). Anecdotal evidence is subject to a number of different types of bias including selection bias, confirmation bias and evaluation bias. The introduction of any bias in any research limits the amount of trust the reader can place in the results.

Finally, anecdote, and subsequent publication of a case study, is often incomplete with the case study only reporting the period of improvement. For example, one might provide an essential oil blend to treat acne and following topical treatment for a week, the lesions begin to clear. The case study reports that this blend of oils was successful. However, there are often variables, reported by the client or not, that reduce the probability that the treatment has cured the acne. For example, the client may be using topical or oral prescription medication – it is possible that one or a combination of both may be of benefit. The client may have changed their diet which may also have an effect on the skin of people suffering acne lesions. They may have come to the practice at a particularly stressful time which has resulted in acute symptoms (for example, exams), but then the stress trigger is removed, and the symptoms resolve; at the next stress trigger, the lesions may return. Acne is cyclical in nature – it can be acute, chronic, mild or severe, and symptoms can naturally resolve, but the condition is still present; it is difficult to conclude then that the topical essential oil prescription had any impact at all. However, a well-designed clinical trial and statistical analysis will resolve these issues.

Do we need more research?

There is a paucity of good clinical research in the fields of aromatherapy and essential oil research, and the primary reason for this is the lack of funding for such research. There are some studies claiming efficacy, however they are often methodologically flawed (Vickers, 2000, Agnew et al., 2014), meaning that the research design does not support the results. Studies are often subject to bias because they are under powered (there are not enough participants in the study to infer that something worked), or there are issues with the methodology. There is a catalogue of bias that can limit the results of apparently strong clinical research. It is important to highlight here that if the research is not methodologically sound, then the results are not automatically trustworthy.

Good clinical research is a prospective investigation to explore the effect of a treatment or intervention, which allows researchers to measure clinical effect using validated instruments. The publication of a study protocol holds researchers to account, meaning they cannot stray from their plan, without having to be transparent about the deviation. The design of clinical research is all about rigor – everything must be transparent so the reader can determine the quality of the research, and whether the findings can or should be implemented into their practice.

There are some very well-designed studies reporting positive outcomes. It is not all doom and gloom! For example, a recent meta-analysis reported on the effect of enteric coated peppermint oil on global symptoms and abdominal pain associated with IBS (Alammar et al., 2019). While they highlight some areas of concern, including attrition bias (excessive loss of participants without any explanation in one study) and bias related to the industry funding for research (that the published research is conducted by a stakeholder with a vested interest in the outcome in one study), the authors are confident that these generally well-designed studies prove that peppermint oil is an efficacious treatment for the symptoms of IBS.

Clinical research – the bigger story

Lack of clinically sound research is then often misinterpreted as evidence of no effect. A good example of this is a recent article that investigated why around half of people with cancer choose not to use CAM whilst undergoing treatment (Beatty et al., 2012). In this Australian focus group study, the authors report that legitimacy of advice and lack of evidence (no reported statistics to state that if you do “this” your risk of cancer will be reduced by “this” much) were barriers. However, there is some strong evidence showing benefit for anxiety and depression, improved sleep, well-being and reduction of nausea and vomiting associated with treatment (Boehm et al., 2012, Lua et al., 2015).

You may be thinking, ‘I have helped cancer sufferers manage facets of the disease and have observed successful outcomes’. This kind of anecdotal evidence is promising, and it is this kind of published case-study evidence that is often the basis of much larger, rigorous studies. The reason why it remains anecdotal is because it is unlikely you have measured the effect. Nor have you replicated the research amongst hundreds, if not thousands of cancer patients, to ensure that this positive outcome is due to the application of the treatment, and not something else. This does not diminish the results of the treatment for your client, but it is not rigorous evidence.

The challenge we have in aromatherapy is that because aromatherapy treatment is patient centred and holistic, it is difficult to measure one treatment across a whole population. It is a challenge, but it is not impossible! Please do not think that a rigorous, scientific framework does not accommodate essential oil interventions. It is all about being creative.

So, it is important that further research is conducted so that treatment is more widely available to people, and not just those who can afford to pay for it physically, financially and emotionally.

Evidence-based practice – what will it do for me?

There is no doubt that there are challenges associated with the implementation of research to practice. However, once you are familiar with the methods of analyzing and interpreting research, there will be considerable benefits for all parties. First, previously held clinical knowledge will either be confirmed or challenged, potentially leading to a change in practice. As well as the skill of critique, you will soon also learn how to utilize outcome measurements thus providing clients with some evidence of how a treatment is working or offer justification for tweaking treatment plans. Providing an evidence-based practice will increase the professional profile of both the practitioner and the practice. In turn, this may drive clients to your business via word of mouth and ultimately all of this will help increase clinical revenue (Jones et al., 2013, Paterson et al., 2013). The aim of an evidence-based practice is not to restrict aromatherapy practice, rather to support it to its full clinical potential.

Conclusion

There is a now need for aromatherapists to adjust their attitudes towards science, and overhaul approaches to practice. Aromatherapy (along with many other CAM practices) now needs to move away from expert-based to evidence-based practice. While it may not be the popular opinion, developing a strong evidence base, and applying this in the clinical setting, will help to promote aromatherapy as a reliable, rigorous, viable, accessible therapeutic intervention, rather than one that dwells on the fringes of healthcare, and is subject to biased and redundant criticism.

References

Agnew, T., Leach, M. & Segal, L. 2014. The clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of essential oils and aromatherapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris: A protocol for a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20, 399. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23829810

Alammar N., Wang, L., Saberi, B. et al 2019. The impact of peppermint oil on the irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of the pooled clinical data. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19, 21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6337770/pdf/12906_2018_Article_2409.pdf

Barnett, A. G., Dobson, A. J. & Van Der Pols, J. C. 2004. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34, 215-220. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15333621

Beatty, L., Koczwara, B., Knott, V. & Wade, T. 2012. Why people choose to not use complementary therapies during cancer treatment: a focus group study. European Journal of Cancer Care, 21, 98-106. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21848581

Boehm, K., Bussing, A. & Ostermann, T. 2012. Aromatherapy as an adjuvant treatment in cancer care – a descriptive systematic review. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 9, 503-18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3746639/pdf/AJT0904-0503.pdf

Bradley, J. 2012. From ‘trust us, we’re doctors’ to the rise of evidence-based medicine. Available: https://theconversation.com/from-trust-us-were-doctors-to-the-rise-of-evidence-based-medicine-10608 .

Dawes, M., Summerskill, W., Glasziou, P. et al 2012. Sicily statement on evidence-based practice. Second International Conference of Evidence-Based Health Care Teachers and Developers, 2005. BMC Medical Education 5 (1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC544887/pdf/1472-6920-5-1.pdf

Fischer, F. H., Lewith, G., Witt, C. M. et al 2014. High prevalence but limited evidence in complementary and alternative medicine: guidelines for future research. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 14, 46-46. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3931324/pdf/1472-6882-14-46.pdf

Jones, M. L., Cifu, D. X., Backus, D. & Sisto, S. A. 2013. Instilling a research culture in an applied clinical setting. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94, S49-S54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23140580

Lua, P. L., Salihah, N. & Mazlan, N. 2015. Effects of inhaled ginger aromatherapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 23, 396-404. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26051575

Merriam-Webster 2019. Anecdotal Evidence. In: Merriam-Webster (ed.).

Simundic, A.-M. 2013. Bias in research. Biochemia medica, 23, 12-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900086/pdf/biochem_med-23-1-12-3.pdf

Vickers, A. 2000. Why aromatherapy works (even if it doesn’t) and why we need less research. The British Journal of General Practice, 50, 444-445. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1313720/pdf/10962780.pdf

Marvelous article, thank you!

Really appreciated the rationale of this article, thank you. However, it is concerning that those institutions we may have placed great faith in for unbiased and objective methodology are now compromising the case! Of note In Australia are the recent reviews on CAM in respect to health fund rebates, naturopathy and as you also mentioned as a basis for removing CAM studies from universities. Research and thus trust, in evidence base, can and is being manipulated on all sides!

Really great and useful information. Thanks!!

This is an interesting article. I am currently trying to work out details to do a study in a perioperative area using lavender for anxiety PRE-OPERATIVE and peppermint post opertaive for nausia. I am coming accross bariers in my attempts to start the research. this article gives me insights. I also read some of the resources at the end of your writing.

We are glad to hear this article has been helpful! If you are able to conduct your research successfully, we would love to hear your results. Feel free to share them with us at support@tisserandinstitute.org. All the best, Shane Carper