By Robert Tisserand

Note: below is a link to a full article, along with an Executive Summary in six languages.

Nature is complex. A single essential oil can contain dozens of constituents, each one of which, alone, has certain properties. How do we make sense of such complexity in nature? We often turn to patterns, to broad categories, just to give us a “rough idea” of what’s going on. And sometimes this works well enough. But what if our “rough idea” is more wrong than right? You may not realize it, but much of the information taught and written about concerning essential oils is based on a flawed idea called Functional Group Theory (FGT).

Nature is complex. A single essential oil can contain dozens of constituents, each one of which, alone, has certain properties. How do we make sense of such complexity in nature? We often turn to patterns, to broad categories, just to give us a “rough idea” of what’s going on. And sometimes this works well enough. But what if our “rough idea” is more wrong than right? You may not realize it, but much of the information taught and written about concerning essential oils is based on a flawed idea called Functional Group Theory (FGT).

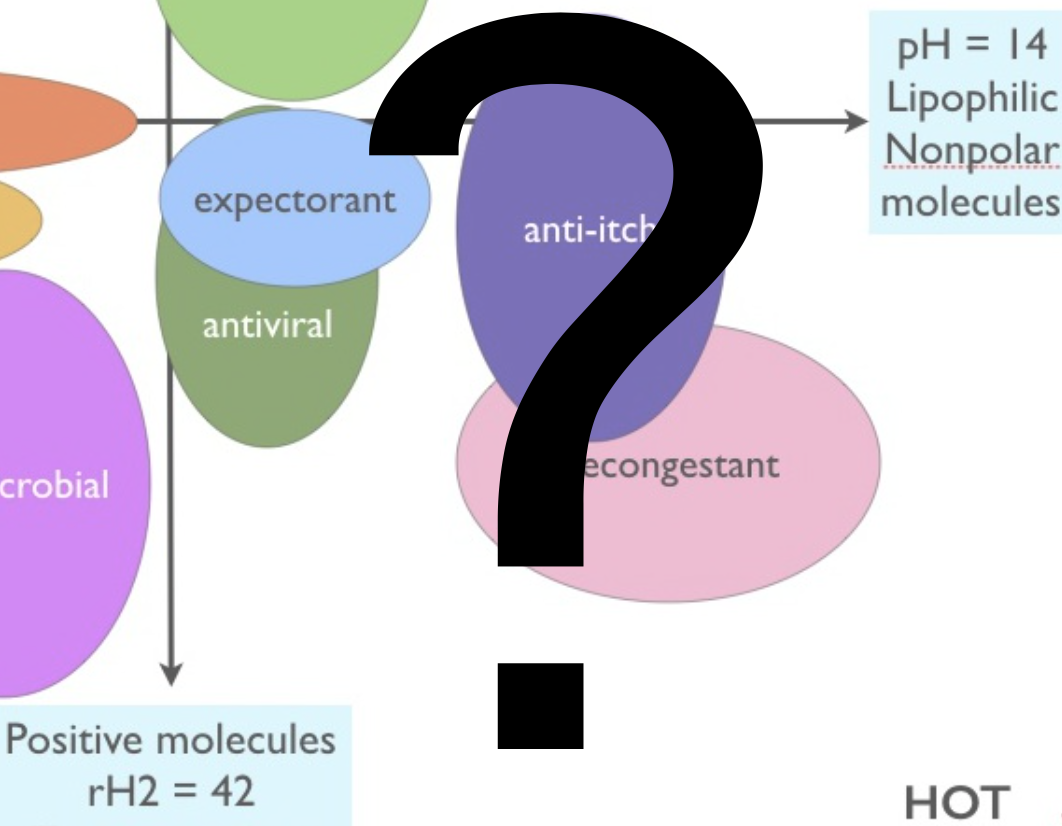

Essential oil constituents can be categorized according to their functional group, or chemical family. Such categories include alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, esters, phenols and more. For some 30 years, FGT has been used as a shortcut to understanding the actions of essential oils in the body. Students learn the properties of each functional group, which essential oils are high in which molecules, and which functional group each molecule belongs to.

However, while this categorization makes sense in terms of chemistry, it turns out that it is not an accurate way to predict or describe the therapeutic properties of essential oil constituents. This is partly because FGT was originally based on a long-debunked hypothesis, and partly because current research shows that the properties of essential oil constituents do not fall into such neat categories.

Marco Valussi, Andrea Cont, Joy Bowles and I spent two years writing a comprehensive explanation for why FGT is not a useful tool to learn or predict essential oil properties. Instead, we propose an approach that more accurately reflects the science and that is, in the end, simpler. Studying the properties of constituents can be extremely useful, but these should be studied individually, rather than in (functional) groups. Abandoning FGT does not mean the therapeutic activities of a constituent need to change, so long as they are based on evidence of effect, and not on assumption.

Executive Summary in English, PDF

Résumé de l’article en Français, PDF

Sintesi del’articulo en Italiano, PDF

日本語の要約

Bravo! This is amazing! Table 8 is a stunning compilation of research by constituent and therapeutic action. Question: For each row in this table, does the entry represent research that was conducted on only the single isolated constituent mentioned, or could the research have also included additional constituents that contributed to the therapeutic action?

Thank you Kathy! The research cited is all on single constituents.

What a great work, I’m so excited to read it! Thank you very much Mr Tisserand.

“Debunking” is a big word for a theory that guided us all these years, and thanks to it we healed many of our infections and diseases. You are a very respected person in your field and your words are always quoted in many publications and aroma classes etc. I personally have your book, and i look into it whenever i have any doubt of a particular essential oil etc, i also took a course in your institute which benefited me a lot. However, i find “Debunking” the FGT is not adding any value to the world of aromatherapy.

Thank you for commenting. Debunking was not our initial aim, and the word only appeared towards the end of the two years it took to write the article. But, in hindsight, I can’t think of a more appropriate term. To “debunk” is to expose the falseness of an idea, and ultimately, I believe this is what we did, and that it was very much needed.

If we perhaps agree to disagree on the use of “debunking”, I hope you found the article itself to be a valuable contribution to the world of aromatherapy, especially the Table that lays out the properties of individual monoterpene alcohols. We are constantly learning more and more about how essential oils interact with the human body, and the teaching and practice of aromatherapy needs to evolve with new information.