“If you feel like you are insignificant, try spending a night with a mosquito in the room.” ~various

They are hard to avoid, in nature and in the news, and they are a cause of annoyance at best, and of a serious health caution at worst. Mosquitoes, or to be more precise, a few species in the genera Aedes, Anopheles and Culex, are reacting to the rapidly changing climate in ways that make their presence known to us. Even without the transmission of diseases such as malaria, Zika, or dengue fever, dealing with the itchy, swollen bites can make your days miserable. As someone who’s blood seems to be a favorite treat for these little suckers, trust me, I know!

The good news is that essential oils can help us in fighting off these insects, and we have research to back this up. Plus we can harness their aromatic powers to alleviate the inflammation and itch from a bite.

Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes, or “little flies” based on the origin of their name, are small flying insects of the family Culicidae. The whole family comprises over 3,500 species. Females of most species feed on the blood of various vertebrates, and many are specialized to feed off a particular host. Male mosquitos do not bite and live off a diet of plant juices such as nectar.

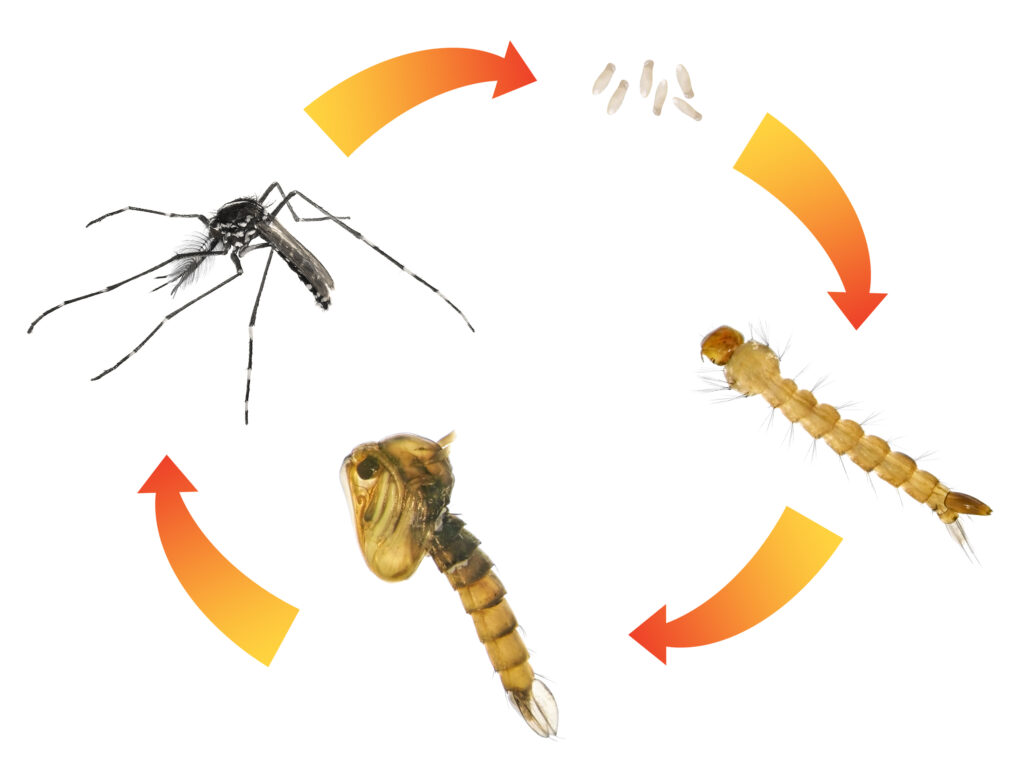

Their life cycle includes egg, larva, pupa and adult stages, with the eggs and larvae living in standing water. Mosquitoes are an important part of the food chain, providing nutrition to other insects, fish and birds. They thrive in warm to hot climates so long as they have access to even a small body of water.

When feeding, a female mosquito will insert its long mouthpiece, called a proboscis, into the skin, piercing one of the surface capillaries and sucking blood. Some species filter out the less nutritious fluids as they suck, discarding droplets from their belly.

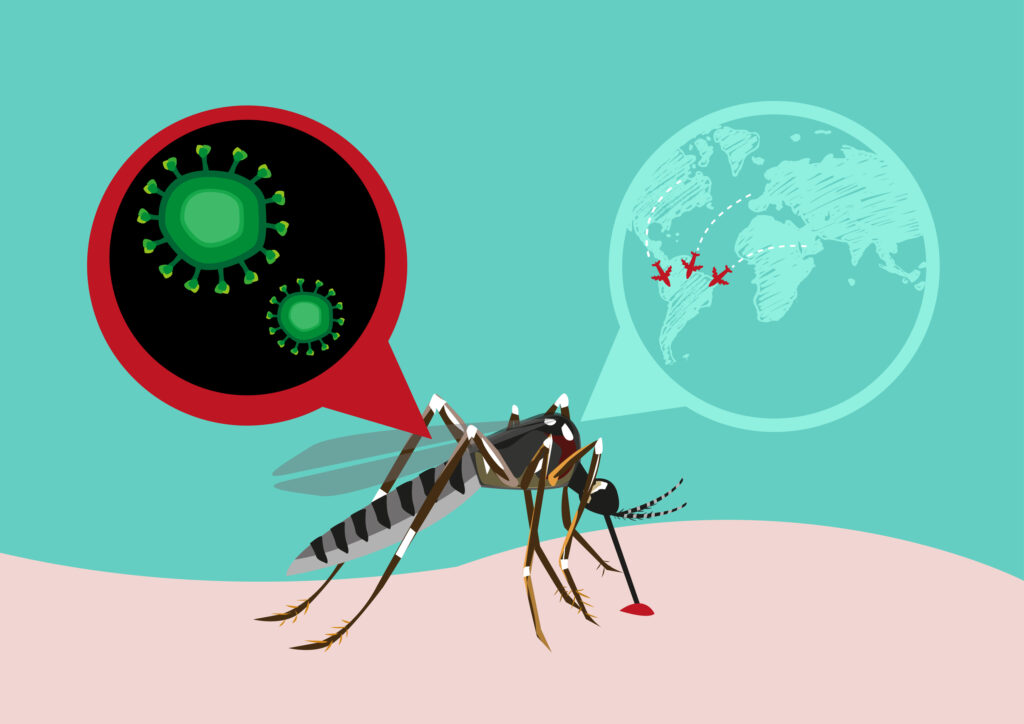

Their blood diet makes female mosquitoes a suitable vector for pathogens – viruses and parasites. With their long proboscis playing the role of a “dirty needle”, pathogens are transmitted into us through the infected mosquito’s saliva. Our immune system reacts to this invasion, resulting in an inflamed and itchy bump. The number of people who die every year of mosquito-borne diseases – about one million – is alarmingly high and is rising as the insect’s hunting grounds have been expanding due to our warming climate.

It may not be the mosquitoes themselves that cause malaria and other diseases, but by controlling their population, and preventing bites with the use of repellents and mechanical barriers, we can keep those illnesses at bay – or at least minimize their impact.

Different species, different stages

Of the thousands of species living on Earth only a very limited number poses any risk to humans. These include the genera Aedes, Anopheles and Culex, with the most notable species being Aedes aegypti, aka the Yellow fever mosquito, and various Anopheles species – all carriers of malaria.

In order to be useful, population control and repellent strategies need to target both the appropriate species and the life-stage of the insect. An adult A. aegypti may not respond the same as an Anopheles larva, for example, and an ovicide (intended to kill the eggs) may not work on other life stages.

Vector diseases

According to the CDC, mosquitoes are “the world’s deadliest animal”, but this need qualification as mosquitoes do not kill directly. It’s not the insect itself, but the pathogens it carries and transmits to its hosts that cause illness and death. A mosquito act as a disease vector – or transportation system – for bacteria, viruses and parasites that wouldn’t otherwise be able to infect the host.

Bubonic plague, for example, is a vector disease that was transmitted by flea bites. Rats were blamed for the Black Death epidemics, but the rodents were merely a vector for the fleas which, in turn, were a vector for Yersinia pestis – the plague bacteria.

This doesn’t mean that we should no longer rely on mosquito control in order to stop the spread of those diseases. It just allows us another layer of understanding on how to approach the control. Some solutions involve driving away those mosquito species that are responsible for the transmission of certain pathogens, and replacing them with another species.

Next we’re going to look at some of the most significant mosquito-borne diseases.

Malaria

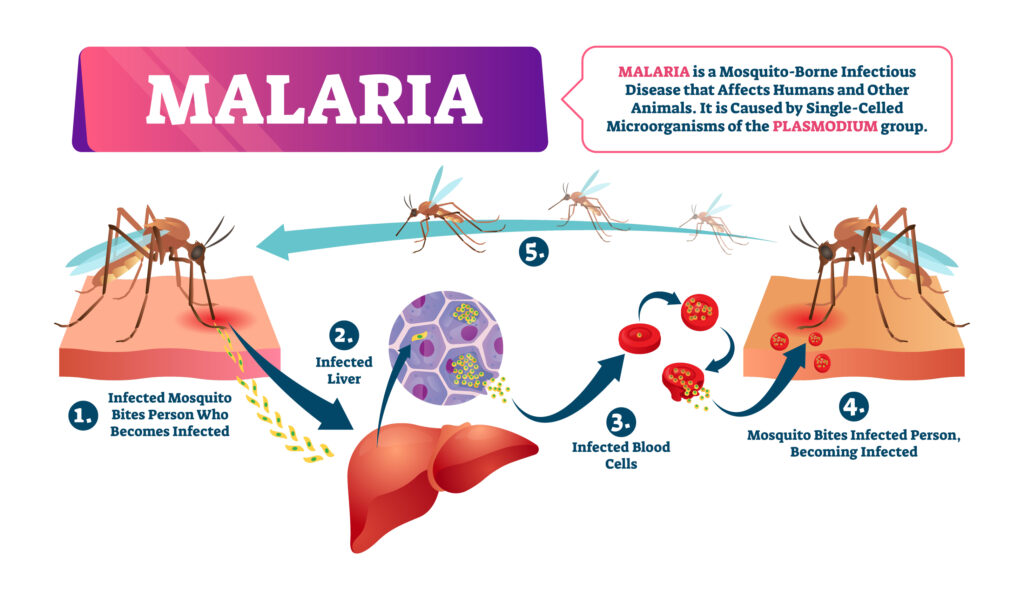

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by Plasmodium parasites (Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale and P. knowlesi) transmitted by mosquitoes in the Anopheles genus (mainly Anopheles coluzzi, A. gambiae, A. funestus and A. nili). Plasmodium is a genus of single-celled, protozoan parasites that take advantage of both mosquito and human hosts during various life stages. They get transferred into humans through infected mosquito saliva. In humans they first attack liver cells before moving into the bloodstream where they proceed to infect red blood cells. From the blood the parasites may be taken in by another mosquito, continuing the life cycle. Malaria is more common in tropical and sub-tropical regions, but with rapidly warming temperatures both the host mosquito and the parasite are beginning to broaden their geographical footprint.

Malaria symptoms occur during the blood infection stage, and include fever and severe chills, accompanied with general discomfort, headaches, fatigue and nausea. The fever and chills may suddenly appear in “attacks”, with the infected person experiencing extreme fluctuations in body temperature. While the symptoms usually manifest within weeks of infection, some Plasmodium species can lay dormant in a body for a time. Malaria is likely to be more severe in young children, infants and older adults, and in severe cases the disease is fatal. In 2021, an average of 1,300 children under the age of five died of malaria every day, and such a death toll makes malaria a high priority for public health measures.

Malaria symptoms occur during the blood infection stage, and include fever and severe chills, accompanied with general discomfort, headaches, fatigue and nausea. The fever and chills may suddenly appear in “attacks”, with the infected person experiencing extreme fluctuations in body temperature. While the symptoms usually manifest within weeks of infection, some Plasmodium species can lay dormant in a body for a time. Malaria is likely to be more severe in young children, infants and older adults, and in severe cases the disease is fatal. In 2021, an average of 1,300 children under the age of five died of malaria every day, and such a death toll makes malaria a high priority for public health measures.

The successful treatment of malaria depends on early detection and diagnosis, and includes plant-derived medicines based on either artemisinin, derived from sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua), or quinine, which is present in the bark of the cinchona tree, or in feverfew. Prevention plays a crucial role in managing the diseases globally. Preventative measures range from avoiding mosquito bites by using mosquito nets and repellents, to prophylactic medicines, to newly developed vaccines.

Zika

The world became more aware of the Zika virus during the Rio de Janeiro Summer Olympics, which coincided with a higher occurrence of the infection. The virus is spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes species, which are very common in temperate regions where they are active during the warm months.

Symptoms of Zika infection include fever, rash, headache and joint pain. More importantly, it can be transmitted during pregnancy causing a birth defect known as congenital Zika syndrome, which includes microcephaly (an abnormally small head). This can cause further health issues later in life depending on the impact on brain development.

There is currently no treatment for Zika infection, but cases remain relatively rare and the infection itself is not life-threatening. Prevention includes avoiding mosquito bites by using nets and repellents.

Those other diseases

Dengue fever, chikungunya, West Nile Virus and yellow fever (named because of the jaundice that appears for some people infected with the virus) all cause fevers and symptoms that are associated with fevers, such as headache, muscle ache, nausea and fatigue. There is no treatment for any of these viral infections, so the best you can do is prevent infection by reducing the risk of being bitten by an infected mosquito, and manage symptoms in case you do get infected. The good news is, apart from yellow fever, people rarely die from these infections, and there is a vaccine for yellow fever.

Aside from pathogens affecting humans, mosquitos are also responsible for the transmission of Eastern equine encephalitis and Western equine encephalitis – viral infections affecting horses. These infections are rare, and so are other livestock mosquito-borne diseases.

https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/distribution.html

Mosquito control

Even though regions with a temperate climate may be relatively safe from mosquito-borne diseases, an uncontrolled mosquito population is more than just a summer nuisance. Luckily there are several strategies we can employ: we can use physical barriers, apply repellents, and/or kill off mosquitoes during their various life stages.

Physical barriers and repellents

One of the easiest strategies to avoid being bitten is to use physical barriers – from nets in windows or over your place of rest, to clothes worn when walking in a mosquito-infested area. In cases where total coverage is not possible, we can turn to the power of repellents. Repellents prevent an insect from landing on or entering into a particular area.

They work by diffusing a substance into the area we wish to protect. This applies to both larger spaces (patios, gardens, etc.) that can be protected using a diffuser, a candle, or an area spray, and to personal protection. In either case we want to be protected from mosquitoes without putting our own health at risk, and luckily for us, essential oils can provide safe protection.

Repellents and the mosquito sense of smell

“You must smell good to them” was something I heard often as an explanation for why I was covered in red spots while my companions were not, even though we shared the same spaces. And in a similar vein, some of the home repelling strategies include eating more vitamin B, nutritional yeast, or, if you’re so inclined, drinking more beer – supposedly to make you smell less enticing. While vitamin B supplementation has not proved to be effective, being attractive to mosquitoes does indeed depend on them tracking your smell.

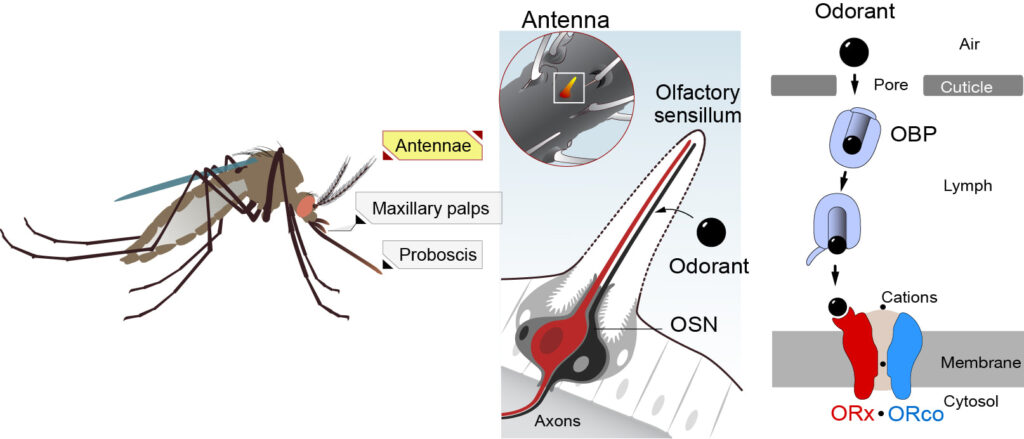

It has been said that “terpene” is the world’s most spoken language. While our sense of smell is one of the five senses we use to navigate the world around us, virtually all life uses chemical communication in some form. This is true for mosquitoes as well, since they make use of volatile organic compounds to locate their next source of food. They have olfactory receptors similar to ours, except theirs are located on their antennae, and are especially adapted to detect carbon dioxide or human skin odors. Repellents mask our odor and confuse the mosquito’s sense of smell, effectively rendering us invisible to it.

We’re just beginning to understand mosquito olfaction, and the researchers in Younger Lab are working hard to decode this in order to create even more efficient and targeted repellents. In the meantime we can take advantage of using the volatile compounds in essential oils to at least confuse if not completely shut off the mosquito “nose”.

In the United States, most products that are going to be marketed as skin-applied repellents must undergo a registration process with the EPA, which includes evaluation and approval for human safety and effectiveness. The EU has a similar process, and repellents are regulated by the ECHA (European Chemicals Agency). Similar to sunscreens, for a product to be labelled as a repellent it needs to undergo some testing.

All the standard tests of repellent efficacy make use of human volunteers exposed to caged female mosquitoes and counting the number and frequency of bites. You can read about different testing methods here.

One of the EPA standard tests is appropriately called the “arm-in-cage assay”. This requires a volunteer to put their arm into a small cage equipped with two plexiglass walls for observation. The arm is covered except for a testing area on the forearm, which is covered in a repellent, usually followed by a control assay (same volunteer, no repellent applied). The cage contains a number of adult female mosquitoes – sometimes thousands – and researchers count the frequency of bites/prodding of the skin. There may be some modulations to the test, but they all involve some form of human skin exposure to mosquitoes. What is measured is both potency and duration, in other words how many bites occur within a determined period of time. All the data presented here for essential oils is based on similar research.

The most useful essential oils

One of the reasons that plants produce volatile compounds is for their own pest control – either by repelling the pest itself, or by calling in predators that feed on that pest. It therefore makes complete sense for us to turn to the plant world for tools that can help us with the same challenge. Essential oils are a promising resource for repellents as they “are less harmful to human beings and to the environment” (de Souza et al, 2019). Because most essential oils evaporate fairly quickly any repellent needs to either be reapplied every 1-2 hours, or used in conjunction with a controlled release medium.

Many essential oils have been tested for their repellent abilities, especially as the world recognizes the increasing threat of mosquito-borne diseases. Review papers are available that list dozens of essential oils and compare their potency (da Silva & Ricci-Júnior, 2020; Asadollahi et al, 2019; de Souza et al, 2019). This article will list some of the more interesting oils, but if you wish to explore the research, make sure to look for these three factors:

- Species tested

- Percent of protection

- Duration of protection

Some essential oils have proved to be so effective that they are listed as EPA registered repellents. There are other promising candidate oils for repellency, and some that work to curb the mosquito population on multiple fronts.

EPA registered essential oils

The essential oils that have been tested and registered with the EPA are:

– Catnip oil (Nepeta cataria)

– Citronella oil (either Cymbopogon nardus or C. winterianus)

– Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (Corymbia citriodora)

The last one is different to pure Lemon Eucalyptus essential oils as it has been manipulated to increase its content of PMD (p-menthane-3,8-diol). PMD naturally occurs in essential oils, and is a registered repellent in its own right with an efficacy similar to that of DEET (the most commonly used insect repellent). This means that Lemon Eucalyptus essential oil (unmanipulated) is potentially a good repellent as well with both citronellal (typically 65%) and PMD (typically 2.5%) being present, although it has not been tested and approved by EPA.

Catnip oil seems to be the most potent of the group, and while it can run expensive, a little goes a long way. A 0.1% concentration was almost twice as effective as 0.1% DEET on Aedes aegypti landings, and a 1% concentration stayed effective for almost as long as 1% DEET (Reichert et al 2019).

Catnip oil seems to be the most potent of the group, and while it can run expensive, a little goes a long way. A 0.1% concentration was almost twice as effective as 0.1% DEET on Aedes aegypti landings, and a 1% concentration stayed effective for almost as long as 1% DEET (Reichert et al 2019).

You can read about EPA registered repellent products here.

Other promising candidates

The oils mentioned here have been identified in the currently available research as promising and potent enough to be considered in your formulation. Some are selected for their similarity with already established repellent oils, some because they have consistently shown to be strong candidates in their own right.

Cinnamon bark, Clove, Peppermint, Lemongrass and Geranium

Both Cinnamon bark (Cinammomum verum) and Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) oils have shown efficacy in research, both as repellents and as pesticides, killing off various stages of mosquito development.

Luker et al (2023) compared Cinnamon bark, Clove, Peppermint, Geranium and Lemongrass as repellents agains A. aegypti. Each oil was applied at 10% in a lotion. Clove oil was the most potent with complete protection lasting 112 minutes. Cinnamon bark and isolated geraniol (the major constituent (80%) of Palmarosa oil) provided protection for over an hour. Peppermint, Geranium and Lemongrass were the next in line for duration, followed by Spearmint and Citronella.

Turmeric, Mandarin, Eucalyptus globulus, Ylang Ylang

These may be among the more surprising choices, though they also appear in several research papers and show promising results in repelling either Aedes or Anopheles species. Mandarin (Citrus reticulata) showed very good potential – with both the peel and leaf oil providing protection. The peel oil was more efficient, preventing 100% of mosquito landings for 30 minutes (Haris et al, 2023).

These may be among the more surprising choices, though they also appear in several research papers and show promising results in repelling either Aedes or Anopheles species. Mandarin (Citrus reticulata) showed very good potential – with both the peel and leaf oil providing protection. The peel oil was more efficient, preventing 100% of mosquito landings for 30 minutes (Haris et al, 2023).

Turmeric (Curcuma longa), Ylang Ylang (Cananga odorata) and Eucalyptus globulus essential oils have also been repeatedly tested against the two mosquito species, and compared to the oils mentioned in the previous section they may be more pleasant to the humans using them (da Silva & Ricci-Júnior, 2020).

Challenges with application

While the research is promising, it’s important to note that the concentrations studied are often significantly above the recommended safe levels for dermal application of essential oils, especially if we consider the need to reapply once the protection time expires. To work with the safety limitations you can:

- Use the oils that show good efficacy at low dilutions, such as Catnip, or those that have few safety precautions and short-term application poses lower risk (Geranium, Citronella).

- Important maximums for application to the skin are: Cinnamon bark 0.1%, Clove 0.5%, Lemongrass 0.7%, Ylang-Ylang 0.8%.

- Use lower dilutions than researched, although this means lowering the protective potential and the need to reapply more often.

- Instead of the skin, apply repellents to your clothes and mosquito nets.

- Diffuse the oils into the environment.

Another challenge to using essential oils as repellents is the fact that they evaporate quickly. This means that they either need to be reapplied every 1-2 hours, or we need to be using delivery systems that prolong their effect. New research is looking into nanoencapsulation and microemulsions, as well as the potential to incorporate repellent substances directly into fabric (da Silva & Ricci-Júnior, 2020).

A note on Neem oil

Neem oil, a fatty oil derived from Azadirachta indica, is a noted and researched mosquito repellent. The oil has a potent smell, and as we already know that is one of the repelling strategies. A study conducted in 2021 by Aidoo et al. concluded that a cream containing 17.5% neem seed oil significantly reduced the number of mosquito landings while not inducing skin irritation.

In a 2023 review, Chatterjee et al. determined that neem oil works as an overall mosquito control agent as it can disrupt all life stages of the insect. The active agent in the oil has been determined as azadirachtin, though the volatile profile of the oil also plays a role in its repellent action.

This means that adding neem oil to your mosquito formulation may be a good idea. If you are not familiar with neem, words used to describe its odor include sulfur, diesel fuel, garlic, peanuts and licorice, though it is perhaps not as stinky as it sounds.

How to make/use essential oils

Now that we know which essential oils are likely to work well, we need to look at how to best put them to use,

-

-

- Environmental diffusion (candles, reed diffusers, diffusers)

-

If you’re looking to protect a larger area, say during a camping trip or at a gathering, environmental diffusion is the best tool to use. The challenge is to sustain the concentration of essential oil high enough for a prolonged period of time. This is why a one-time spray may not be sufficient, and you should look for sustained release tools, such as electric or reed diffusers, or candles. Just make sure to refill the diffusers for sufficient coverage. It makes sense to place the source of repellent at the perimeter of the protected area, creating an invisible protective wall.

For outdoor spaces the safety risks of sustained diffusion are minimal, though people with sensitivities to odorants should avoid sitting near the source of the scent. If you want to protect a closed space while having a window open, and a net cover is not an option, consider putting the repellent source on the windowsill to minimize the risk of overexposure indoors.

-

-

- Personal application (sprays, lotions, gels)

-

Environmental diffusion isn’t always possible. In scenarios that involve a lot of moving (hikes, walks), or when attending an outdoor event, it’s more efficient to use personal protection applied directly to clothes or skin. Repellent essential oils can be incorporated into gels and lotions for topical application, and sprays can be used for both your body and your attire. The challenges here include formulation safety and longevity of effect.

When formulating a product we need to keep in mind both the safety and efficacy of the active ingredients, making sure the concentration of essential oils is high enough to achieve the desired effect, but not too high that it would cause skin irritation. We also need to make sure the medium is formulated safely and efficiently. For example when creating a spray or a lotion, we need to make sure the essential oils are fully incorporated, and the formula is also adequately preserved. The simplest solution is to use a single vegetable oil with little to no odor, such as fractionated coconut oil. You can combine it with neem oil for extra repellency.

When formulating a product we need to keep in mind both the safety and efficacy of the active ingredients, making sure the concentration of essential oils is high enough to achieve the desired effect, but not too high that it would cause skin irritation. We also need to make sure the medium is formulated safely and efficiently. For example when creating a spray or a lotion, we need to make sure the essential oils are fully incorporated, and the formula is also adequately preserved. The simplest solution is to use a single vegetable oil with little to no odor, such as fractionated coconut oil. You can combine it with neem oil for extra repellency.

There are mosquito stickers/patches (small adhesive patches) and bracelets on the market. The patches often contain essential oils, presumably they work well, and they take care of the formulation challenges. However the bracelets have not proven effective. Patches with essential oils have been on the market for some time, with the chief application being for inhalation in a hospital setting. Using the mechanism of a small adhesive patch that is imbued with an essential oil to provide protection from mosquitoes seems like a good idea.

Another challenge is the longevity of the applied repellent. Essential oils are by their nature volatile, and the active compounds will evaporate, rendering the protection useless in 1-2 hours. This means the repellent needs to be reapplied frequently. There is some research into using microencapsulation for delayed release. This technology is currently outside of the scope of an artisan formulator, but we can take advantage of any products available on the market that make use of it. We can also use fatty oils, which will help retard evaporation of the essential oils, but will not be good for clothing.

Killing

A sure-fire way to prevent mosquito bites is to make sure there are no mosquitoes to bite you in the first place. There are many population control strategies targeting different life stages. When deciding which strategy is best for your situation, you may need to identify the species and the life stage you want to target, as some substances work more universally than others.

The challenges always include determining the right concentration for the best effect with minimal negative impact, either on the environment or on you. Delivery systems are an important consideration, and if we want to include essential oils in our pesticide regimen, focusing on ovicidal and larvicidal action may be more practical than trying to target flying adults.

Ovicides and Larvicides

Ovicides are substances that destroy eggs. There are synthetic chemicals that are sometimes used, however the issues with these are increasing resistance in the mosquito population as well as secondary toxicity to non-target species. Essential oils have been explored as an alternative, and have shown a good promise as ovicides. A 2023 study published in Nature tested oils of Cinnamon bark, Lemongrass and Bitter Orange against eggs of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Cinnamon bark and Lemongrass showed very good efficacy, with the best results obtained from Cinnamon bark in combination with geranial (a major constituent of Lemongrass oil). This combination proved lethal to the eggs at 10,000 ppm (roughly 1% concentration). All the essential oils tested also proved to be non-toxic or only mildly toxic to non-target aquatic life (Moungthipmalai et al, 2023).

Larvicides target the larval stage of development. Synthetic larvicides have similar issues to ovicides – mosquito larvae tend to grow resistant to the substance, which is also detrimental to other aquatic life. Essential oils have been investigated as a suitable alternative as they are biodegradable, generally non-toxic at the levels used, effective at killing off the larvae. Perhaps due to their variable and complex composition, mosquitoes are not becoming resistant to essential oils at the same rate as to conventional larvicides.

A 2017 review by Andrade-Ochoa and colleagues looked at the larvicidal potential of essential oils and their constituents by reviewing available literature. They reported on the larvicidal activity of 81 essential oils against mosquitoes in the Culex, Aedes and Anopheles genera, as published in research between 2010 and 2015. The most effective oils that are also commercially available include Turmeric (Curcuma longa), Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis) and Lemon (Citrus limon). Lemongrass showed good efficacy as well, and Cinnamon bark was moderately effective.

A 2017 review by Andrade-Ochoa and colleagues looked at the larvicidal potential of essential oils and their constituents by reviewing available literature. They reported on the larvicidal activity of 81 essential oils against mosquitoes in the Culex, Aedes and Anopheles genera, as published in research between 2010 and 2015. The most effective oils that are also commercially available include Turmeric (Curcuma longa), Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis) and Lemon (Citrus limon). Lemongrass showed good efficacy as well, and Cinnamon bark was moderately effective.

Both eggs and larvae live in water, and so any substance that is used to curb the population needs to be applied to the affected body of water. While there are commercially available water pesticides based on essential oils, you may also have some success using hydrolats. As they are water soluble, they can be sprayed on the water surface without harmful side effect to other organisms living in the water or using it to drink.

Another biologically safe population control tool is Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (BTI) a bacterium which produces a substance toxic to mosquito larvae but safe for any other insect or animal. These can be purchased in the form of “mosquito bits” or “mosquito dunks” that are submerged in the water we wish to protect. Very useful for small areas such as bird baths and water fountains.

Traps and adulticides

As well as getting rid of mosquito eggs and larvae, we can use several strategies to control the adult population. There are physical traps, which lure the insect in, either by light or by using other bait. Traps are essentially the opposite of a repellent. Once inside the trap, the mosquito is usually caught on a sticky surface where it dies of starvation. Some traps are powered by electricity and kill insects with electric current.

Insecticide sprays can also be used to kill mosquitoes, however they tend to be the most extreme option to reach for, and are troubled with the same issues as ovicides and larvicides – they tend to be toxic to other forms of life. Some essential oils have been researched for their powers to kill adult mosquitoes of various species. A 2019 review by M. A. de Souza et al. identified Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) as the most effective in killing adult mosquitoes. Other notable oils mentioned include Caraway (Carum carvi), Zedoary (Curcuma zedoaria) and Garlic (Allium sativum). A Cajuput (Melaleuca cajuputi) aerosol showed promising activity as well.

Treatment for bites

As well as repellents and insecticides, essential oils can bring relief to those who have been bitten. Anti-inflammatory, antihistamine and anti-itch essential oils are especially useful. An ideal product would be gel-based and contain peppermint or lavender. Since we’re talking about localized application on a small area, you can use 5% or more of essential oil. If you’re not comfortable with how to formulate a gel, you can also use a fatty oil as a medium.

Summary

Mosquitoes of the Aedes, Anopheles and Culex species not only feast on human blood, but also provide a suitable vector for dangerous viruses and parasites. With warmer weather and longer summer periods, their hunting grounds are expanding and so is the need to control their population.

Many essential oils have been studied and have proved their usefulness. Citronella, Catnip and Lemon Eucalyptus oils are accepted as registered repellents in the USA. Other useful oils include Cinnamon bark, Clove, Peppermint, Lemongrass, Geranium and Spearmint, as well as Turmeric, Mandarin and Ylang Ylang. Some essential oils can be used as pesticides on top of being repellent, notably Cinnamon bark, Clove and Lemongrass. Generally speaking, essential oils provide a more environmentally friendly solution, as they are biodegradable and seem to be less toxic to the non-target species.

In addition to their role in prevention, essential oil-based preparation can be used to manage symptoms of mosquito bites, alleviating both the itch and inflammation resulting from our immune system’s reaction to mosquito saliva.

References

Aidoo, O., Kuntworbe, N., Owusu, F. W. A., & Nii Okantey Kuevi, D. (2021). Chemical composition and in vitro evaluation of the mosquito (Anopheles) repellent property of neem (Azadirachta indica) seed oil. Journal of Tropical Medicine, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5567063

Andrade-Ochoa, S., Sánchez-Torres, L. E., & Nevárez-Moorillón, G. V. (2017). Aceites esenciales y sus componentes como una alternativa en el control de mosquitos vectores de enfermedades. Biomédica, 37(2), 224–267.

Asadollahi, A., Khoobdel, M., Zahraei-Ramazani, A., Azarmi, S., & Mosawi, S. H. (2019). Effectiveness of plant-based repellents against different Anopheles species: A systematic review. Malaria Journal, 18(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-3064-8

Barnard, D., Bernier, U., Xue, R., & Debboun, M. (2006). Standard methods for testing mosquito repellents. Insect Repellents, (January), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420006650.ch5

Bezayit Solomon, Tsige Gebre-Mariam & Kaleab Asres (2012) Mosquito Repellent Actions of the Essential Oils of Cymbopogon citratus, Cymbopogon nardus and Eucalyptus citriodora: Evaluation and Formulation Studies, Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants, 15:5, 766-773, DOI: 10.1080/0972060X.2012.10644118

Chatterjee, S., Bag, S., Biswal, D., Sarkar Paria, D., Bandyopadhyay, R., Sarkar, B., … Dangar, T. K. (2023). Neem-based products as potential eco-friendly mosquito control agents over conventional eco-toxic chemical pesticides-A review. Acta Tropica, 240(February), 106858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2023.106858

da Silva, M. R. M., & Ricci-Júnior, E. (2020). An approach to natural insect repellent formulations: from basic research to technological development. Acta Tropica, 212, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105419

de Souza, M. A., da Silva, L., Macêdo, M. J. F., Lacerda-Neto, L. J., dos Santos, M. A. C., Coutinho, H. D. M., & Cunha, F. A. B. (2019). Adulticide and repellent activity of essential oils against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) – A review. South African Journal of Botany, 124, 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2019.05.007

Deng W, Li M, Liu S, Logan JG, Mo J. Repellent Screening of Selected Plant Essential Oils Against Dengue Fever Mosquitoes Using Behavior Bioassays. Neotrop Entomol. 2023 Jun;52(3):521-529. doi: 10.1007/s13744-023-01039-z. Epub 2023 Mar 16. PMID: 36928838; PMCID: PMC10181966.

Ghayempour S, Montazer M. Micro/nanoencapsulation of essential oils and fragrances: Focus on perfumed, antimicrobial, mosquito-repellent and medical textiles. J Microencapsul. 2016 Sep;33(6):497-510. doi: 10.1080/02652048.2016.1216187. Epub 2016 Oct 4. PMID: 27701985.

Haris, A., Azeem, M., Abbas, M. G., Mumtaz, M., Mozūratis, R., & Binyameen, M. (2023). Prolonged repellent activity of plant essential oils against dengue vector, Aedes aegypti. Molecules, 28(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28031351

Lee, M. Y. (2018). Essential oils as repellents against arthropods. BioMed Research International, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6860271

Luker, H. A., Salas, K. R., Esmaeili, D., Holguin, F. O., Bendzus-Mendoza, H., & Hansen, I. A. (2023). Repellent efficacy of 20 essential oils on Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and Ixodes scapularis ticks in contact-repellency assays. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28820-9

Moungthipmalai, T., Puwanard, C., Aungtikun, J., Sittichok, S., & Soonwera, M. (2023). Ovicidal toxicity of plant essential oils and their major constituents against two mosquito vectors and their non-target aquatic predators. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29421-2

Osanloo M, Firoozian S, Zarenezhad E, Montaseri Z, Satvati S. A Nanoliposomal Gel Containing Cinnamomum zeylanicum Essential Oil with Effective Repellent against the Main Malaria Vector Anopheles stephensi. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2022 Jun 22;2022:1645485. doi: 10.1155/2022/1645485. PMID: 35784810; PMCID: PMC9242819.

Pavela R, Maggi F, Iannarelli R, Benelli G. Plant extracts for developing mosquito larvicides: From laboratory to the field, with insights on the modes of action. Acta Trop. 2019 May;193:236-271. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.01.019. Epub 2019 Jan 31. PMID: 30711422.

Silvério MRS, Espindola LS, Lopes NP, Vieira PC. Plant Natural Products for the Control of Aedes aegypti: The Main Vector of Important Arboviruses. Molecules. 2020 Jul 31;25(15):3484. doi: 10.3390/molecules25153484. PMID: 32751878; PMCID: PMC7435582.

Soroh A, Owen L, Rahim N, Masania J, Abioye A, Qutachi O, Goodyer L, Shen J, Laird K. Microemulsification of essential oils for the development of antimicrobial and mosquito repellent functional coatings for textiles. J Appl Microbiol. 2021 Dec;131(6):2808-2820. doi: 10.1111/jam.15157. Epub 2021 Jun 11. PMID: 34022108.

Reichert, W., Ejercito, J., Guda, T., Dong, X., Wu, Q., Ray, A., & Simon, J. E. (2019). Repellency assessment of Nepeta cataria essential oils and isolated nepetalactones on Aedes aegypti. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36814-1

Useful links and websites:

Mosquitoes:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ragxMHl6n6c

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosquito

Information on diseases and their spread:

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/outdoor/mosquito-borne/default.html

https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/symptoms/index.html

https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/en/learn/mosquito-borne-diseases

https://www.cdc.gov/zika/about/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/biology/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/malaria/index.html

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/malaria/symptoms-causes/syc-20351184

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_equine_encephalitis_virus

Information on quinine and artemisinin:

https://xerces.org/blog/wild-quinine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artemisinin

Mosquito sense of smell:

https://www.youngerlaboratory.org/research

https://www.bu.edu/articles/2022/mosquitoes-have-a-bizarre-sense-of-smell/

https://blogs.biomedcentral.com/bugbitten/2019/04/19/receptors-help-mosquitoes-smell-us/

Repellents:

https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents/find-repellent-right-you

https://www.epa.gov/minimum-risk-pesticides/conditions-minimum-risk-pesticides#tab-1

http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/citronellagen.html#howwork

https://eu.biogents.com/official-standard-methods-guidelines/

Am glad to be part of this page