Aromatherapy’s unique appeal is that something natural and fragrant can have beneficial effects on both body and mind at the same time. This therapeutic duality was recognized independently by ancient civilizations that incorporated aromatic plants into traditional medicines, rituals and everyday life long before distillation and essential oils were known. However, it was not until the 20th century that René-Maurice Gattefossé, a French chemist and perfumer, identified aromatherapy as a distinct discipline (Gattefossé, 1937).

In broad terms, aromatherapy is the intentional use of the volatile constituents from aromatic plants in their distilled, expressed or extracted forms to promote health and well-being. It has a broad scope of applications, ranging from comfort and enjoyment to the treatment of kidney stones. Perhaps the term aromatherapy is over-suggestive of healing with aroma (fragrance), although that was not how Gattefossé envisioned it in his seminal book Aromathérapie: Les Huiles Essentielles Hormones Végétales (1937), where it was applied with a clear medical scope. Unlike some other complementary and alternative therapies, aromatherapy has a scientific base that is gaining credibility. Growing interest in the medical approach to aromatherapy from both consumers and practitioners has led to an increasing need to understand how it works. This includes mechanisms of action, dose or dilution, modes of administration and the dynamic between feel-good and medicine. What is actually going on?

Essential Oils

Essential oils are the primary therapeutic tool of aromatherapy. Due to their history and tradition, infused oils (macerates), resins (incense) and hydrolats (hydrophilic part of the distillate) from aromatic plants are also used, although they are considerably less concentrated than essential oils. In principle, concentrated aromatic extracts obtained by use of a solvent, such as absolutes, resinoids, oleoresins and CO2 extracts, could also be used aroma-therapeutically. However, only CO2 extracts seem to have truly caught on as a therapeutic means, likely due to the excellent preservation of the natural properties of plants and the absence of solvent residue. Because aromatic extracts contain both non-volatile and volatile constituents, their use may be considered as a bridge between phytotherapy and aromatherapy, also referred to as phytoaromatherapy. The use of whole plants or their parts, along with their tinctures, teas and other hydrophilic extracts is generally considered to be herbal medicine or phytotherapy.

The term aromatherapy has been used as a marketing strategy for a plethora of cosmetics and scented products. The amount of total essential oil or other aromatic extract in many commercial products is very low and commonly overpowered by added synthetic aromachemicals. Commercialization of aromatherapy (Barcan, 2014) has distorted its public perception and caused some aromatherapists to avoid the term aromatherapy altogether. However, there is a trend of niche cosmetic products in the market containing higher concentrations of natural aromatic materials, which may have aromatherapeutic benefit.

How Does Aromatherapy Work?

There is some controversy with regard to how aromatherapy works. In the scientific literature, it is well accepted that essential oils and individual constituents can work both pharmacologically and psychologically. These are considered the two fundamental modes of action, and both can affect physiological processes.

Pharmacological mechanisms

After entering the body through the nose, skin or internal routes, individual constituents selectively bind to specific targets in cells and tissues, most notably proteins or cell membranes. By modifying their functional properties, bioactive constituents can directly affect physiological processes in the body. For example, they may reduce inflammation by modifying specific signaling pathways in immune cells or help calm the mind by binding to specific receptors in nervous tissue.

Pharmacological mechanisms are dose-dependent and substance-specific, which means that a particular constituent will exert similar effects in everyone. A single constituent may bind to a variety of different targets, but with different strengths (affinities) and selectivity. As complex mixtures of chemicals that follow specific pharmacological paths, essential oils can exert multiple pharmacological actions at the same time with potentially synergistic interactions (Gertsch, 2011; Maffei, Gertsch, & Appendino, 2011). However, not all of the effects observed in vitro will necessarily confer actual therapeutic benefits.

Correct dosing is vital to achieving a clinically relevant effect. The therapeutic window is an optimal dose range that produces a therapeutic response without causing significant adverse effects — in most individuals. The dose depends on many factors, such as method of application and form of dosage, the bioavailability of active substances, their pharmacological potency and toxicity, and whether the expected effect is local or systemic. The chemical diversity of essential oils, along with a general lack of pharmacological data, further complicate the issue of proper dosage. The pharmacodynamics of essential oil constituents (their effects and how they work) has only been a subject of extensive research for the last 10 to 15 years. While much is known, we are only beginning to get a full sense of the biological mechanisms and therapeutic potential.

Psychological effects

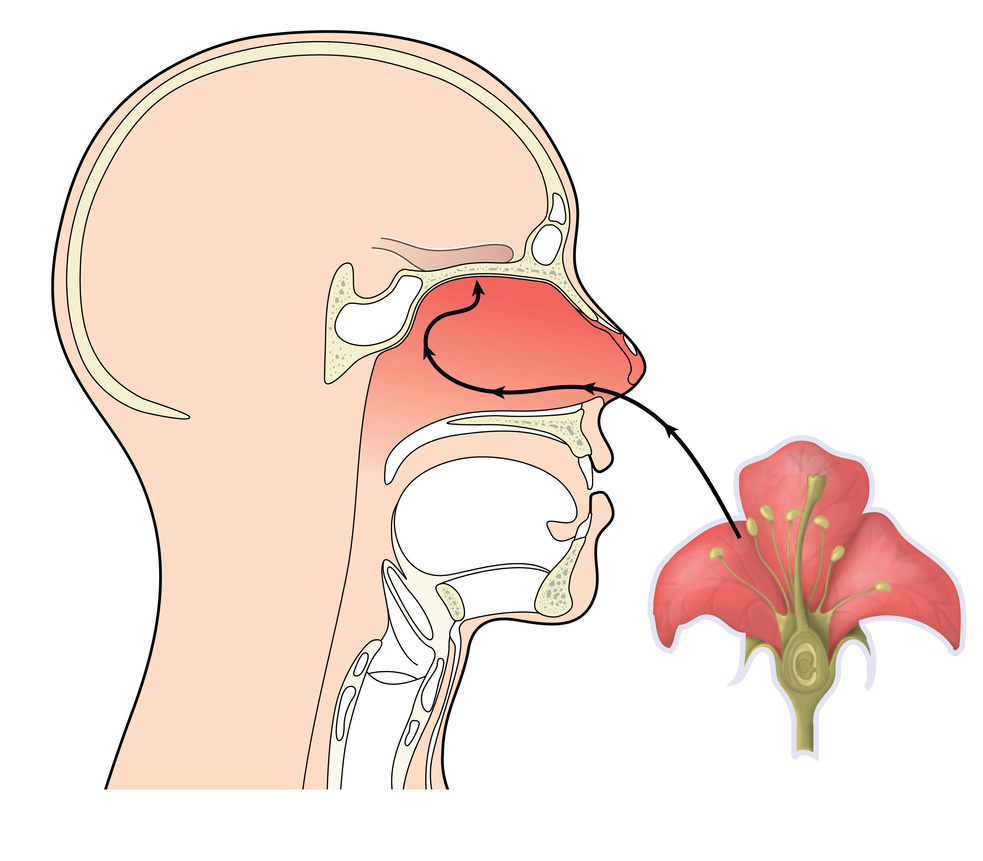

Rather than directly affecting physiological processes, the sense of smell mediates the psychological effects of essential oils. Once odorant molecules bind to olfactory receptors in the upper part of the nasal cavity, they initiate a cascade of neurological processes that activate different parts of the brain and finally lead to the conscious experience of smell. The perception of smell feeds back to the neurophysiological processes to modulate mood, emotions, cognition, physiological arousal and behavior. Due to the inherently subjective nature of odor interpretation and a fundamentally different mechanism compared to pharmacological effects, psychological effects are not substance-specific. This means that the same essential oil will not always have the same psychological effect.

Rather than directly affecting physiological processes, the sense of smell mediates the psychological effects of essential oils. Once odorant molecules bind to olfactory receptors in the upper part of the nasal cavity, they initiate a cascade of neurological processes that activate different parts of the brain and finally lead to the conscious experience of smell. The perception of smell feeds back to the neurophysiological processes to modulate mood, emotions, cognition, physiological arousal and behavior. Due to the inherently subjective nature of odor interpretation and a fundamentally different mechanism compared to pharmacological effects, psychological effects are not substance-specific. This means that the same essential oil will not always have the same psychological effect.

Perfumer J. Stephan Jellinek (1997) lucidly summarized the psychological effects of odors and classified them into three distinct mechanisms: hedonic, semantic and placebo. In other words, odors exert psychological effects through pleasantness, associations and the expectations associated with them.

Hedonic — Pleasantness

Semantic — Association

Placebo — Expectation

Psychological effects can be genuinely therapeutic and not just feel-good. For example, odors were found to help reduce pain perception, anxiety, cravings and enhance feelings of social connectedness and optimism (Herz, 2007; 2016).

Odors can evoke memories and emotions regardless of whether or not they are of natural origin. A scientific discipline that examines the psychological effects of smell is sometimes known as aromachology (aroma + psychology), though its scope is obviously different from aromatherapy. Psycho-aromatherapy on the other hand considers the pharmacological effects of inhaled constituents as well but is only concerned with fragrances of plant origin.

The psychological effects of odor are more context-dependent and dynamic than the pharmacological effects, even though both may take place at the same time. The overall effect of a fragrance is a complex and inextricable combination of psychological and pharmacological factors (Heuberger, Stappen, & Rudolf von Rohr, 2017; Peace Rhind, 2014, 2015), which makes aromatherapy intriguingly complex and its overall effects difficult to predict

The ‘functional group’ approach

In their book L’aromatherapie Exactement, Pierre Franchomme and Daniel Pénoël (1990/2001) proposed a unifying framework for explaining how essential oils exert psychophysiological effects based on the functional groups (the chemical families) of their constituents. This model, also known as “functional group theory,” proposes that constituents bearing the same functional groups would exert similar effects (for example, esters are spasmolytic, alcohols are stimulating and so on).

However, the theory is highly unreliable — even if only used as a general guideline — because it makes pharmacological assumptions solely on the basis of constituent chemistry classification, without looking at what actually happens in the body. In a recent review of empirical evidence, Robert Tisserand and colleagues (2018) found no structure–effect correlations according to functional group and molecular structure for most constituents. Exceptions include phenols (strongly antimicrobial, antioxidative), sesquiterpene lactones (skin allergens) and furanocoumarins (phototoxic). However, the biological activity of these molecules is based non-specific mechanisms.

The holistic approach

Holistic aromatherapy is not clearly defined. Often it is a collage of different traditional medicines and philosophies from around the world that have been linked to aromatherapy throughout its development. Knowledge systems such as Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda, the ancient Greek doctrine of humors and various herbal, religious, ritual and intuitive uses of aromatic plants, along with their historical and symbolic meanings, were either incorporated as an adjunct to aromatherapy ー as its spiritual extension or a tool for diagnosis ー or used to further develop models for how essential oils exert so-called subtle or energetic effects.

The holistic approach considers the person as an integrated whole of body, mind and spirit. Jennifer Peace Rhind (2015) observes that, although diverse, holistic approaches commonly share the qualities of individual treatment and a vitalistic element. Vitalism presupposes the existence of a vital force (energy or spirit) as an organizing principle behind life processes beyond the known physical forces. As a theory of life (and not as an antithesis to reductionism), vitalism lost scientific credence in the early 20th century, mostly because it does not add to the explanation for the complexity of life (Garrett, 2013). Practitioners of holistic aromatherapy, however, find a deeper meaning in belief, ritual and intimate engagement with plants and essential oils. In light of the reinforcing evidence-based approach to aromatherapy, the tension between its esoteric and hardline scientific versions (Barcan, 2014) continues to stir up discussions about the place of aromatherapy.

Modes of Application

Although some authors characterized aromatherapy exclusively in terms of inhalation (Buchbauer, Jirovetz, & Jäger, 1991; Lis-Balchin, 1998 as cited in Lis-Balchin, 2016), and some still do (Schneider, Singer, & Singer, 2019), a more commonly held view within the aromatherapy community include dermal and, to a limited degree, internal administration.

Inhalation

Inhalation is the most popular method of aromatherapy (Dornic et al., 2016; Ratajc, 2017). It is easy to practice, noninvasive and allows full appreciation of the fragrance, while also enabling relatively good absorption of constituents into the body. Inhalation can be personal (direct) or ambient (indirect), with active or passive diffusion of volatiles depending on whether they are released by a convective force or passively. In general, active personal inhalation is more appropriate for treating the respiratory system and delivering bioactive constituents into the body, while ambient diffusion is preferred for enhancing the mood and potentially for disinfecting the room against viruses although ambient diffusion protocols have also been successfully used in clinical trials, for example on sleep (Lillehei & Halcon, 2014; Hwang & Shin, 2015).

Inhalation is the most popular method of aromatherapy (Dornic et al., 2016; Ratajc, 2017). It is easy to practice, noninvasive and allows full appreciation of the fragrance, while also enabling relatively good absorption of constituents into the body. Inhalation can be personal (direct) or ambient (indirect), with active or passive diffusion of volatiles depending on whether they are released by a convective force or passively. In general, active personal inhalation is more appropriate for treating the respiratory system and delivering bioactive constituents into the body, while ambient diffusion is preferred for enhancing the mood and potentially for disinfecting the room against viruses although ambient diffusion protocols have also been successfully used in clinical trials, for example on sleep (Lillehei & Halcon, 2014; Hwang & Shin, 2015).

With inhalation, the constituents can either exert therapeutic effects through the olfactory system and the sense of smell or by entering the body via the lung mucosa, nasal mucosa and intranasal pathway (nose to brain), thus reflecting psychological and pharmacological modes of action. Some authors (e.g., Herz, 2009) expressed skepticism regarding pharmacologically relevant levels of active constituents in the blood after inhalation, maintaining that therapeutic effects are exclusively psychological. However, studies on mice (Buchbauer et al., 1991; Kovar et al., 1987) and humans (Moss & Oliver, 2012) showed correlations of cognitive and behavioral measures with the blood concentration of active constituents. Moreover, clinical remission of brain glioma (a type of tumour) was observed after direct inhalation of perillyl alcohol (Chen, da Fonseca, & Schönthal, 2018), indicating that pharmacological effects following inhalation are plausible.

Topical administration

Dermal administration can provide therapeutic benefits through absorption into the skin, transdermal delivery with local or systemic effects and via the combined effect of touch and smell in massage with essential oils. Lower doses (0.1-5%) are usually applied in aromatherapy massage, where the primary aim is to induce physical and mental relaxation that can exert powerful physiological response by lowering stress levels, reducing blood pressure and improving well-being (Price & Price, 2012).

In cosmetics, essential oils and aromatic extracts are mainly used for their antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties, as well as for their pleasant smell. For pain, inflammation, infections, injuries and other medical conditions in the skin or subdermal tissues, the concentration needed depends on the oil used, the nature of the condition and a person’s age. Higher concentrations may be necessary, such as in the treatment of acne, where a concentration of tea tree oil below 5 percent may not be effective (Hammer, 2015).

Generally, lipophilic molecules with molecular mass up to 500 can permeate the upper layer of the skin (stratum corneum) and be absorbed into deeper layers of the skin and circulatory system (Benson, 2012). As small molecules up to about 300 Da and with medium-to-high lipophilicity, many essential oil constituents can penetrate the skin relatively well compared to other types of compounds. On uncovered skin, up to 10 percent of the applied dose is absorbed and may reach the bloodstream (Tisserand & Young, 2014).

Friedl and colleagues (2015) compared the concentration of 1,8-cineole in the human plasma and blood after inhalation and dermal application. Although the dermal dose — which was applied with a thermoplastic foil to prevent evaporation and controlled for pulmonary absorption — was triple the inhalation dose, peak systemic concentrations within a 45-minute measurement range were very low (8,0-46,3 ng/mL) and only about one-tenth of those absorbed via inhalation. The authors explained these results by the accumulation of 1,8-cineole in subcutaneous fatty tissue, which acted as a reservoir and slowed down its release into the blood.

Unfortunately, transdermal delivery of essential oil constituents has been studied more in terms of their capability to enhance the skin permeation of other drugs, rather than as bioactive constituents themselves. Studies that demonstrate systemic effects after transdermal delivery usually do not control for pulmonary absorption and olfaction. Therefore, it is difficult to assess whether the observed systemic therapeutic effects are caused by the pharmacological effects from dermal or pulmonary absorption, the massage itself (when not controlled for) or the psychological effects of smell.

Studies controlling for pulmonary absorption and olfaction demonstrated systemic effects of some essential oils on the autonomous nervous system, measured by physiological parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate or breathing rate (Hongratanaworakit, 2009a, 2009b). However, for specific medical conditions, local therapeutic effects on skin and underlying joints and muscles may be more effective. Local delivery ensures higher concentration of active constituents, delivered by a combination of diffusion, regional vascular drainage, and lymphatic and interstitial transport (Doktor, Lee, & Maibach, 2013).

Internal administration

Internal administration includes oral, intranasal, rectal and vaginal routes, and employs targeted dosage forms such as granules, capsules, syrups, sprays, gargles, pessaries and suppositories. The main advantages of internal administration are higher bioavailability of active constituents and control over the applied dose. The disadvantages are potential irritations of mucosal surfaces on the site of administration, hepato- and neurotoxicity, interactions with medications, and gastrointestinal discomfort such as nausea. Another disadvantage is a general lack of safety information over longer periods of administration, for example, due to the accumulation of constituents in fatty tissues and potential delayed effects (Tisserand & Young, 2014).

A specific characteristic of taking essential oils orally, compared to all other modes of administration, is first-pass metabolism (the exception is administration and absorption in the oral cavity). The constituents are absorbed in the hepatic portal system, a series of veins running from the gastrointestinal tract to the liver, where a significant proportion is metabolized before reaching systemic circulation, therefore reducing bioavailability and requiring dose adjustment where systemic effects are needed. Further, instead of being inactivated by the liver, some constituents (such as pulegone, estragole or methyleugenol) are converted into pharmacologically more potent or toxic metabolites (Tisserand & Young, 2014).

Several essential-oil-based drugs are registered on the market, available for oral intake without prescription (see Table). In general, clinical research on internally administered essential oils is not abundant. Therapeutic effects and short-term tolerability were shown for functional dyspepsia (Shams et al., 2015), infantile colic (Alexandrovich et al., 2003), hypotension (Fernández, Palomino, & Frutos, 2014) and intestinal parasites (Force, Sparks, & Ronzio, 2000), to mention a few, and many trials are conducted on extracts and individual constituents.

Table: Some examples of essential-oil-based drugs intended for oral administration

| Name | Active substances and dosage form | Indication | Pharmacological action | Reference |

| GeloMyrtol® | 300 mg rectified essential oils of eucalyptus, myrtle, orange and lemon (mostly 1,8-cineole, limonene, α-pinene) emulsified in enteric-coated (gastro-resistant) soft gelatin capsules | acute bronchitis, sinusitis | mucolytic, expectorant, anti-inflammatory, spasmolytic | Gillissen et al., 2013 |

| Rowatinex® | 67 mg isolated essential oil constituents α-pinene, β-pinene, camphene, borneol, anethole, fenchone, 1,8-cineole mixed with olive oil in enteric-coated (gastro-resistant) soft gelatin capsules | kidney and urinary tract stones, kidney and urinary colics | antilithogenic, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, spasmolytic, analgesic | Romics et al., 2011 |

| Silexan* | 80 mg standardized lavender oil (Lavandula angustifolia) emulsified in soft gelatin capsules for immediate release | subsyndromal anxiety, mild sleep disorders | anxiolytic | Kasper et al., 2018 |

| Colpermin® | 0.2 mL (~187 mg) peppermint oil (Mentha x piperita) mixed with peanut oil in enteric-coated hard capsules for delayed release | irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | spasmolytic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, analgesic | Shams et al., 2015 |

*Silexan is an active ingredient sold under various commercial names.

However, direct translation of the findings into aromatherapy practice may not always be reasonable. In a study by Fernández, Palomino and Frutos (2014) mentioned above, 30 participants ingested 1 mL of rosemary oil three times per day over a period of 44 weeks, which totals almost a liter per person. In addition to being inconvenient and unsustainable over the long-term, the authors reported 17 cases of acute gastroenteritis ー but quite curiously did not consider it to be related to treatment.

Internal administration of essential oils and concentrated aromatic extracts is a matter of controversy in aromatherapy, not just due to a substantial amount of lay advice available online, but also regarding its relation to aromatherapy. Technically, internal dosage forms are akin to standard pharmacotherapy, where pharmaceutical drugs are used for the treatment of medical conditions. The “aroma” component of aromatherapy – the smell and flavor of aromatics – becomes epiphenomenal or even undesired. Moreover, most researchers do not consider research on the internal administration of essential oils to be aromatherapy or aromatic medicine, which is not surprising because they treat essential oils as herbal drugs and thus part of herbal medicine or phytotherapy. Consequently, studies employing internal administration are frequently omitted from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of aromatherapy, and therefore the overall therapeutic potential of essential oils may not be fully evident. Internal administration of essential oils can be considered as yet another area where phytotherapy and aromatherapy intersect.

The Medical Approach to Aromatherapy

The scope of aromatherapy is extremely wide, ranging from feel-good to medicine. The many ways in which plant aromatics can be used to act on the body and mind partially blur the boundaries between cosmetic, hygienic, mood-enhancing, psychotherapeutic and medicinal applications. For example, treatment of acne can be regarded as cosmetic or medicinal, and stress can be approached both pharmacologically and psychologically. Aromatherapy’s complexity is generally a good thing for the consumer as well as the practitioner, because therapeutic benefits can be tackled from different angles and tailored to an individual’s needs while keeping in line with regulations.

However, the breadth of aromatherapy’s applications is also a challenge for the research. The natural variability in the composition of essential oils makes it difficult to reliably reproduce scientific findings. Moreover, it is difficult to control for the psychological effects of fragrance, especially in research protocols employing massage and inhalation. Because effective blinding is hard to establish in clinical trials, many otherwise well-designed studies are evaluated as being of poor quality, and consequently, their clinical relevance is downgraded in systematic reviews (e.g., Lee et al., 2012; Perry et al., 2012). Methodological variability due to the different treatment protocols, outcome measures and diversity of essential oils are added research challenges on top of the hurdle of securing funding for independent research. Together, all this makes quality clinical research of aromatherapy demanding.

‘Soft’ vs. ‘hard’ medicine

Medicine is the science or practice of the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease (“medicine,” n.d.); therefore, application of essential oils or concentrated aromatic extracts to treat a medically diagnosable condition would be considered medicinal use. Aromatherapy’s appeal is that it can be a natural, simple and effective method of self-treatment for minor health issues by noninvasive applications of essential oils. However, consumers also use them for more serious conditions.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to draw a clear line between “soft” therapy suitable for home use, and “hard” medicine. The distinction depends not so much on the type of condition (e.g., infection, inflammation) and mode of administration, but rather on the severity of symptoms, intended dosing and, above all, potential risk. Incidental cosmetic application of an irritant or phototoxic oil to the skin can pose higher risk than targeted medicinal use with proven safety and efficacy One can safely use an over-the-counter product such as Silexan in line with the prescription without specific knowledge of essential oils or thinking of it as aromatherapy. On the other hand, creating an innovative formula for a specific need necessitates ー especially in professional settings ー familiarity with essential oil pharmacology, proper dosing (posology), human physiology, proficient risk-benefit assessment and judgment of the suitability of aromatherapy compared to other treatment options.

Most humans ingest volatile constituents from aromatic herbs, spices, fruits, vegetables and naturally flavored products on a daily basis, where doses are very small. This cannot be regarded as a targeted medicinal use. In addition to their feel-good value on the senses, regularly incorporating plant secondary metabolites in the diet (more generally speaking) can certainly promote a range of nonspecific pharmacological actions, such as antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, carminative, spasmolytic, digestive, choleretic, mucoprotective and more ー also on account of the variety of bioactive constituents not present in essential oils.

Plant secondary metabolites may collectively counteract chronic inflammatory conditions that play a substantial part in many diseases of modern society (such as dementia, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, cancer or irritable bowel syndrome) via numerous weakly binding interactions and synergies (Gertsch, 2016). The many ways in which essential oils, CO2 extracts or hydrolats can be creatively incorporated in food, sweets and beverages for flavoring may add to the overall effect.

Aromatherapy and medicine

Essential oils were included in dispensatories for centuries. Their medicinal use was brought into wider public attention by French pioneers Gattefossé and Valnet, along with the onset of modern aromatherapy. In contemporary (phyto)aromatherapy, branches promoting the medical approach are known as clinical aromatherapy, medical aromatherapy, aromatology and aromatic medicine. Practitioners usually work in private practice, in clinics and hospitals or hospices. Aromatic medicine is recognized in Australia as an independent therapeutic modality whose practitioners are authorized to prescribe essential oils and aromatic extracts for internal administration (but not to diagnose) In most countries, only licensed healthcare practitioners such as medical doctors and pharmacists can legally prescribe essential oils for medical conditions, although regulation, education and use in medical establishments vary considerably among different countries (Price & Price, 2012).

In phytotherapy, organizations such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA), European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP), Commission E (no longer active) and World Health Organization (WHO) Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3, Vol 4 issue monographs on herbal drugs, including essential oils. These organizations overview traditional use, nonclinical research and clinical data for specific indications, along with the appropriate dosage, treatment duration and safety considerations. These data can serve as guidelines for medical doctors, pharmacists and researchers designing clinical trials, and as a reference for marketing and registration of drugs based on traditional use. A systematic overview of the medicinal use of essential oils by indication is detailed in the chapter by Robert Harris in the Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications (2016).

However, most medical doctors are not trained in the use of herbal drugs such as essential oils, and will not readily advise their use unless they are available as registered commercial products. Nonetheless, there is a clear need and consumer expectation for natural health remedies. The wide availability of research data opens the door to unqualified educators and sales representatives — who have a clear commercial interest — to readily advise lay people on the pharmacotherapeutic use of essential oils in a way that appears safe and credible. Any intensive use of essential oils should not be based on ad hoc advice, but rather requires proper knowledge and professional consultation, and should be intended for specific indications with clear outcomes in mind.

Conclusions

Aromatherapy is full of contrasts: objective versus subjective modes of action, holistic versus evidence-based, feel-good versus medicine. Opinions about the scope of aromatherapy also differ to a considerable extent. It will be interesting to see whether aromatherapy will remain a coherent therapeutic modality or further diversify into traditional and increasingly medically oriented applications. The medicinal potential of essential oils is far from fully explored, and research is necessary for expanding knowledge. Ideally, all research should be independent, but unfortunately, commercial interest is its major driving force. Aromatherapy should be the place where independent research, practice and public benefit go hand in hand and interact synergistically.

References

Alexandrovich, I., Rakovitskaya, O., Kolmo, E., Sidorova, T. & Shushunov, S. (2003). The effect of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed oil emulsion in infantile colic: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 9(4), 58-61.

Aprotosoaie, A. C., Hăncianu, M., Costache, I. I., & Miron, A. (2014). Linalool: a review on a key odorant molecule with valuable biological properties. Flavour and Fragrance Journal, 29(4), 193-219.

Barcan, R. (2014). Aromatherapy oils: Commodities, materials, essences. Cultural Studies Review, 20(2), 141-171.

Benson, H.A.E. (2012). Skin structure, function, and permeation. In H. A. E. Benson & A. C. Watkinson (Eds.), Topical and transdermal drug delivery: Principles and practice (pp. 1-22). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Buchbauer, G., Jirovetz, L., & Jäger, W. (1991). Aromatherapy: Evidence for sedative effects of the essential oil of lavender after inhalation. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C, 46(11-12), 1067-1072. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-1991-11-1223

Chen, T., da Fonseca, C., & Schönthal, A. (2018). Intranasal perillyl alcohol for glioma therapy: Molecular mechanisms and clinical development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(12), 3905. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19123905

Doktor, V., Lee, C. M., & Maibach, H. I. (2013). Deep percutaneous penetration into muscles and joints: Update. International Journal of Drug Delivery, 5(3), 245-256. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1289-6_13

Dornic, N., Ficheux, A. S., Roudot, A. C., Saboureau, D., & Ezzedine, K. (2016). Usage patterns of aromatherapy among the French general population: A descriptive study focusing on dermal exposure. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 76, 87-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.01.016

Fernández, L. F., Palomino, O. M., & Frutos, G. (2014). Effectiveness of Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil as antihypotensive agent in primary hypotensive patients and its influence on health-related quality of life. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 151(1), 509-516. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.006

Force, M., Sparks, W. S., & Ronzio, R. A. (2000). Inhibition of enteric parasites by emulsified oil of oregano in vivo. Phytotherapy Research, 14(3), 213-214. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(20000514:3<213::AID-PTR583>3.0.CO;2-U

Franchomme, P., &Pénoël, D. (1990/2001). L’aromathérapie exactement. Limoges, France: Roger Jollois.

Friedl, M., Susanne, M., Heuberger, E., Oedendorfer, K., Kitzer, S., Jaganjac, L., Stappen I., & Reznicek, G. (2015). Quantification of 1, 8-cineole in human blood and plasma and the impact of liner choice in head-space chromatography. Current Bioactive Compounds, 11(1), 49-55. doi: https://doi.org/10.2174/157340721101150804151256

Garrett, B. (2013). Vitalism versus emergent materialism. In S. Normandin & C. T. Wolfe (Eds.), Vitalism and the scientific image in post-enlightenment life science 1800–2010. History, philosophy and theory of the life sciences (127-154). New York: Springer.

Gattefossé, R. M. (1937/1993). Gattefosse’s aromatherapy. New York: Random House.

Gertsch, J. (2011). Botanical drugs, synergy, and network pharmacology: Forth and back to intelligent mixtures. Planta Medica, 77(11), 1086-1098. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1270904

Gertsch, J. (2016). The metabolic plant feedback hypothesis: How plant secondary metabolites nonspecifically impact human health. Planta Medica, 82(11/12), 920-929. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-10834

Gillissen, A., Wittig, T., Ehmen, M., Krezdorn, H. G., & de Mey, C. (2013). A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial on the efficacy and tolerability of GeloMyrtol® forte in acute bronchitis. Drug research, 63(01), 19-27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1331182

Hammer, K. A. (2015). Treatment of acne with tea tree oil (melaleuca) products: A review of efficacy, tolerability and potential modes of action. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 45(2), 106-110. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.10.011

Harris, R. (2016). Phytotherapeutic uses of essential oils. In K. H. C. Başer & G. Buchbauer (Eds.), Handbook of essential oils: Science, technology, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 381-432). Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Herz, R. (2007). The scent of desire: Discovering our enigmatic sense of smell. New York: William Morrow.

Herz, R. S. (2016). The role of odor-evoked memory in psychological and physiological health. Brain sciences, 6(3),22. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci6030022

Herz, R. S. (2009). Aromatherapy facts and fictions: A scientific analysis of olfactory effects on mood, physiology and behavior. International Journal of Neuroscience, 119(2), 263-290. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207450802333953

Heuberger, E., Stappen, I., & Rudolf von Rohr, R. (2017). Riechen und fühlen. Wie geruchssinn, ängste und depressionen zusammenspielen – Neue wege der behandlung. Munderfing: Fischer & Gann.

Hongratanaworakit, T. (2009a). Relaxing effect of rose oil on humans. Natural Product Communications, 4(2), 291-296.

Hongratanaworakit, T. (2009b). Simultaneous aromatherapy massage with rosemary oil on humans. Scientia Pharmaceutica, 77(2), 375-388. doi: https://doi.org/10.3797/scipharm.0903-12

Hwang, E., & Shin, S. (2015). The effects of aromatherapy on sleep improvement: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(2), 61-68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0113

Jellinek, J. S. (1997). Psychodynamic odor effects and their mechanisms: Failure to identify the mechanism can lead to faulty conclusions in odor studies. Cosmetics and Toiletries, 11(9), 61-71.

Kasper, S., Müller, W. E., Volz, H. P., Möller, H. J., Koch, E., & Dienel, A. (2018). Silexan in anxiety disorders: Clinical data and pharmacological background. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 19(6), 412-420. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2017.1331046

Kovar, K. A., Gropper, B., Friess, D., & Ammon, H. P. T. (1987). Blood levels of 1, 8-cineole and locomotor activity of mice after inhalation and oral administration of rosemary oil. Planta Medica, 53(4), 315-318. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-962725

Lee, M. S., Choi, J., Posadzki, P., & Ernst, E. (2012). Aromatherapy for health care: An overview of systematic reviews. Maturitas, 71(3), 257-260. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.018

Lillehei, A. S., & Halcon, L. L. (2014). A systematic review of the effect of inhaled essential oils on sleep. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(6), 441-451. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2013.0311

Lis-Balchin, M. (2016). Aromatherapy with essential oils. In K. H. C. Baser & G. Buchbauer (Eds.), Handbook of essential oils: Science, technology, and applications (2nd ed., 619-654). Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Maffei, M. E., Gertsch, J., & Appendino, G. (2011). Plant volatiles: Production, function and pharmacology. Natural Product Reports, 28(8), 1359-1380. doi: https://doi.org/10.1039/c1np00021g

Medicine. (n.d.) In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/medicine

Moss, M., & Oliver, L. (2012). Plasma 1, 8-cineole correlates with cognitive performance following exposure to rosemary essential oil aroma. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 2(3), 103-113. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125312436573

Peace Rhind, J. (2014). Fragrance and wellbeing: Plant aromatics and their influence on the psyche. London: Singing Dragon.

Peace Rhind, J. (2015). Aromatherapeutic blending: Essential oils in synergy. London: Singing Dragon

Perry, R., Terry, R., Watson, L. K., & Ernst, E. (2012). Is lavender an anxiolytic drug? A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Phytomedicine, 19(8-9), 825-835. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2012.02.013

Price, S., & Price, L. (2012). Aromatherapy for health professionals (4th ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.

Ratajc, P. (2017). Patterns of essential oil use among the Slovenian population: An online survey. 48th International Symposium on Essential Oils (ISEO2017). Abstracts. Natural Volatiles & Essential Oils, 4(3), 130.

Romics, I., Siller, G., Kohnen, R., Mavrogenis, S., Varga, J., & Holman, E. (2011). A special terpene combination (Rowatinex®) improves stone clearance after extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy in urolithiasis patients: Results of a placebo-controlled randomised controlled trial. Urologia Internationalis, 86(1), 102-109. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000320999

Schneider, R., Singer, N., & Singer, T. (2019). Medical aromatherapy revisited—Basic mechanisms, critique, and a new development. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 34(1), e2683. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2683

Shams, R., Oldfield, E. C., Copare, J., & Johnson, D. A. (2015). Peppermint oil: Clinical uses in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases. JSM Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3(1), 1035-1046. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6931/16e195a255da7171d6c869698b2ea458704a.pdf

Tisserand, R., & Young, R. (2014). Essential oil safety: A guide for health care professionals (2nd ed.). London: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Tisserand, R., Valussi, M., Cont, A., & Bowles, E. J. (2018). Debunking functional group theory: Not supported by current evidence and not a useful educational tool. International Journal of Professional Holistic Aromatherapy, 7(3), 7-61.

Wow, what an excellent, in depth, articulate and exceptionally researched article. Thank you so much Petra and the Tisserand Institute for sharing.

Very good to read, but unless you are a qualified medical person, able to take blood, x-ray to cover yourself for insurance purpose, mistakes on internal use could be very expensive if taken to court. Unless you hold a medical degree for any action you take. Regards, Eve Taylor, OBE.

HI tHERE,

i HAVE BEEN SEARCHING HIGH AND LOW AND I’M WONDERING IF YOU CAN TELL ME WHERE I MIGHT BE ABLE TO DOWNLOAD OR PURCHASE A COPY OF THE ROBERT TISSERAND PYCHO-AROMATHERAPY POSTER?

YOUR HELP WOULD BE DEEPLY APPRECIATED

THANK YOU!

Hi Jennifer,

I do not know anywhere it can be purchased – I stopped printing them many years ago!