We live in a world of quick fixes and proclaimed miracle cures, and essential oils have not escaped the proclivity people have in identifying the next magic bullet. Today, as we face issues like increased resistance in bacteria to antibiotics, the therapeutic application of aromatics offers hope to an area where the lack of a solution would mean an unwelcome reminder of much darker days.

Currently, bacteria do not appear to be developing resistance to essential oils, certainly not to the extent they have in relation to antibiotics. This, in combination with their sometimes potent antibacterial action, has encouraged some researchers to consider essential oils as one potential option to counteract an increasing threat to human populations. The CDC is speaking out on the problems that microbial resistance presents. Although the CDC is not yet considering essential oils to address this concern, the power hiding in the molecular makeup of these substances cannot be denied; in fact, modern research is frequently turning new corners that corroborate the widespread belief that essential oils can positively impact the state of human health.

It is therefore no surprise that the antimicrobial power exhibited by oils such as cinnamon bark, oregano, thyme thymol, clove, lemongrass and blends containing these are increasing in prevalence and popularity. The potential of essential oils to address health concerns is being noticed, despite the current lack of governmental oversight in this area. Parents in particular are finding essential oils an appealing alternative to both over-the-counter and prescription medications, and essential oils are promoted to them as a safe replacement for almost anything.

Essential oils are used in several industries although we are used to seeing them discussed in the context of how they can benefit the body. The discussion on their potential health benefits has been circulated in large by network marketing companies whose target audience is families. Home parties where essential oils are advertised as being the answer for everything from the common cold to reducing chemical exposure in the home catch the attention of the health-conscious as a way to better improve their overall health and wellness. One consulting firm, Grand View Research, Inc., projects the essential oil market to surpass $11 billion by the early 2020s (Research, 2016). While the therapeutic use of essential oils only makes up a small fraction of the industry, two of the larger network marketing companies offering them, Young Living Oils, and doTERRA, both claimed to have reached $1 billion in sales revenue in 2015. Given such figures, it is no small surprise that essential oils are finding their way ubiquitously into the home. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of some very necessary cautions.

Children

It is understandable that parents want what is safest and best for their children. Medications can have unpleasant and sometimes dangerous side effects, though all medicines are predicated on the idea that the benefit of using them outweighs the risk of foregoing treatment. But essential oils are not without their own risks and require the same considerations of risk v. benefit. While research can often point to impressive qualities and therapeutic potentials, making use of those benefits must still be done with respect to both the oils’ individual safety and the body’s natural functions.

It is understandable that parents want what is safest and best for their children. Medications can have unpleasant and sometimes dangerous side effects, though all medicines are predicated on the idea that the benefit of using them outweighs the risk of foregoing treatment. But essential oils are not without their own risks and require the same considerations of risk v. benefit. While research can often point to impressive qualities and therapeutic potentials, making use of those benefits must still be done with respect to both the oils’ individual safety and the body’s natural functions.

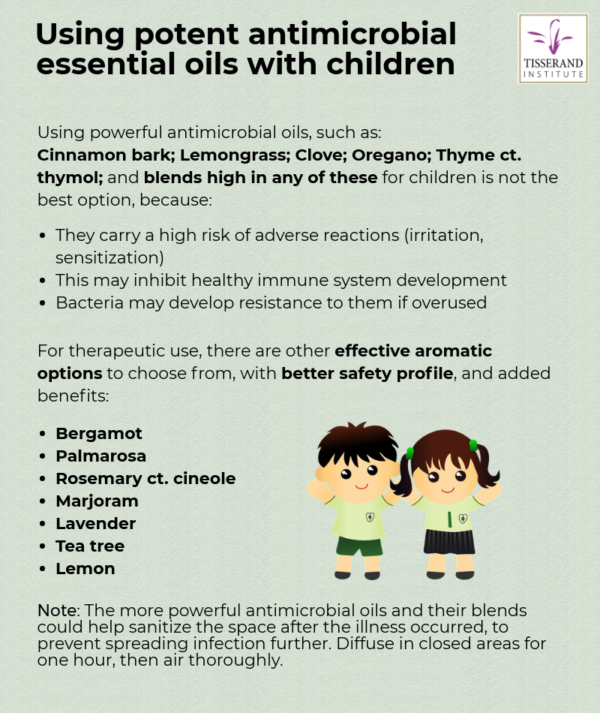

Although some essential oils may be potent antimicrobials, does the way they are currently used preserve the integrity of our children’s health? There may be cause for concern, for three reasons. One, the most potently antimicrobial essential oils also tend to be the most risky in terms of adverse skin reactions (Tisserand & Young 2014). Two, although there is not much evidence so far of bacterial resistance to essential oils, it is almost inevitable that this will eventually happen. And three, though essential oils are often touted as “immune boosting”, there is almost no clinical evidence to support such claims, and in the case of young children, enthusiastic use of essential oils may actually inhibit normal immune development.

The immune system

The immune system is classically divided into two parts: innate (non-specific) and adaptive (specific). The innate immune system is the part we are born with. It is our primary line of defense and includes physical barriers such as the skin and different cellular components, acting immediately upon infecting pathogens (AK LECTURES, 2014). Natural killer cells (NK cells) are part of the innate immune system and while they were originally named for their ability to kill tumor cells, they also attack disease-causing bacteria and viruses.

Despite their action against pathogenic invaders, NK cells can also have an unwanted effect when one of the cytokines they produce, interferon (IFN)-γ, interacts with other cells. This can cause inflammation, leading to an impaired immune response and a decreased ability to fight infection (Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes, & Adib-Conquy, 2017). A rare over-reaction of the immune system to a viral infection, known as a cytokine storm, can be fatal.

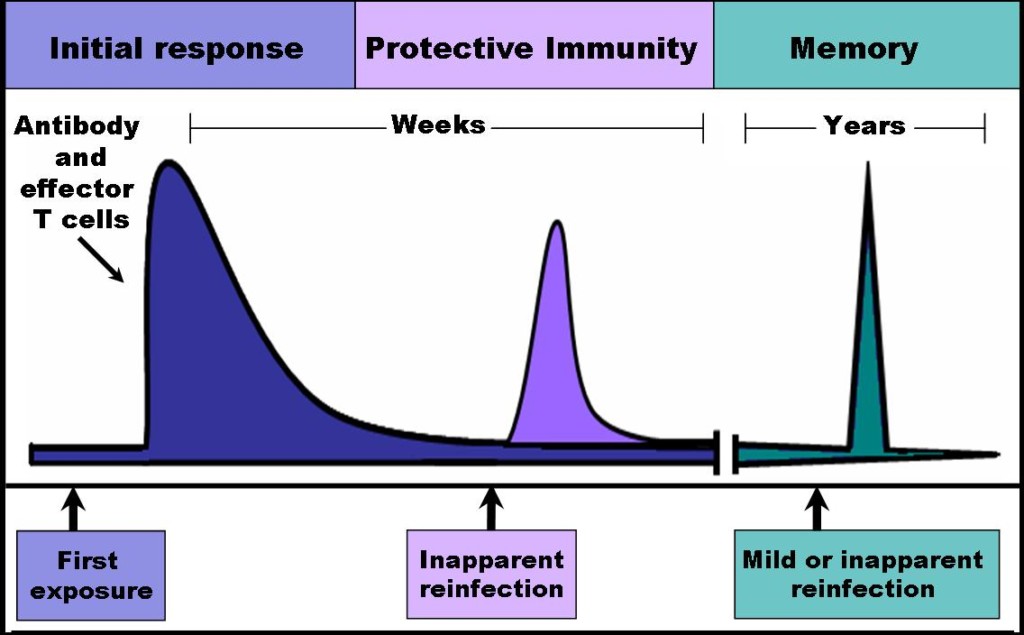

The adaptive immune system, on the other hand, develops its protective capabilities through a series of cellular interactions with antigens and learns through this exposure, so that the body can produce antibodies and recognize future attacks from the same pathogens. Unlike the innate immune system, the adaptive immune system can take days to reach its peak function (AK LECTURES, 2014). Regulatory T cells (Treg) are a part of the adaptive response and are responsible for regulating and suppressing the immune system, preventing an overstimulated response. The appropriate development of these cells is crucial to a child’s health. Dysfunction in Treg has huge implications in autoimmunity, asthma, and other allergic diseases that may develop later in life (Rook et al., 2004).

Young immune systems need exercise

In the case of children, their capability to establish an appropriate immune response to the pathogens in their environment, as well as develop a properly functioning immune system, appears to require certain kinds of exposure. While we do not yet fully understand what is the best combination of microorganisms we should introduce our children to, research on the effect of antibiotics on the immune system has shown that shortening an infection by allowing an external catalyst to remove the pathogens ultimately results in a decreased immunologic memory (North, Berche, & Newborg, 1981). Of course, this does not mean that treating infection should be avoided. It does, however, raise the question of whether reaching for a powerful antimicrobial agent as soon as the first symptoms show up is the best use of these resources. Without the opportunity to take note of and react to pathogens, the immune system cannot create the necessary memory cells that help children fight off recurrent attacks, inhibiting the appropriate development of their immune response.

While essential oils such as lemongrass, cinnamon bark, oregano, thyme thymol and clove may be quite beneficial in the battle against microbes, it does not mean that reaching for them automatically whenever a child is sick represents their

most judicious use, especially when, as we see so frequently today, these powerhouses are being used for even minor colds.

We must ask: does the benefit outweigh the risk? Perhaps not, especially when the current surge in the development of other diseases is considered.

Atopic disease, the hygiene hypothesis, and the “old friends” theory

Atopic disease is on the rise. For decades now, we have seen an increase in illnesses such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever), asthma, and atopic eczema. According to the CDC, 8.6% of children under the age of 18 have been diagnosed with asthma as of 2014 (CDC, 2016). That is up from 3.5% in 1980 (CDC, 2007). The World Health Organization notes that “Asthma is the most common non-communicable disease among children” (WHO, 2016). In the case of skin allergies, the CDC notes that there has been an increase in occurrence between 1997 and 2010, rising from 7.4% to 12.5% during that time (CDC, 2017). Hay fever shows the same upward trend, the number of affected children increasing from 6.9% of children in 1980 to 16.6% by 2009 (CDC, 1994; CDC, 2013).

“Dysfunction in Treg has huge implications in autoimmunity, asthma, and other allergic diseases that may develop later in life (Rook et al., 2004).”

Researchers have questioned why we are seeing a significant increase in these conditions and more interestingly, why these increases are seen more frequently in modernized societies with better access to healthcare. In 1989, David P. Strachan thought he saw a correlation between a higher incidence of common childhood infections, and a lower incidence of atopic disease. Strachan’s idea, dubbed the Hygiene Hypothesis, proposes that fewer infections in childhood, due in increased hygiene, might inhibit the body’s ability to establish a fully functional immune system (Strachan, 1989). Further research, however, shows that it may not be quite that simple.

The Hygiene Hypothesis is based on the idea that too much cleanliness may raise the risk of a child developing an allergy later in life. The hypothesis has been examined from many angles, however no clear links between overzealous hygiene and atopy were established. Interestingly though, studies have shown that children exposed to farming environments seem to fair better when it comes to hay fever, highlighting contact with farm animals, stable environments, unpasteurized milk, etc. It was also noted that this perceived protection against atopy was specific to children who had experienced this exposure in the first years of life as opposed to contact at any age (Bloomfield, Stanwell-Smith, Crevel, & Pickup, 2006).

As Bloomfield et al  (Bloomfield et al, 2016) noted in their review, the name Hygiene Hypothesis should be abandoned, as it implies that cleanliness is bad, while increasing the risk of spreading infectious diseases. They do agree that exposure to microbes is crucial, especially in early age: “The immune system is a learning device, and at birth it resembles a computer with hardware and software but few data. Additional data must be supplied during the first years of life through contact with microorganisms from other humans and the natural environment.”

(Bloomfield et al, 2016) noted in their review, the name Hygiene Hypothesis should be abandoned, as it implies that cleanliness is bad, while increasing the risk of spreading infectious diseases. They do agree that exposure to microbes is crucial, especially in early age: “The immune system is a learning device, and at birth it resembles a computer with hardware and software but few data. Additional data must be supplied during the first years of life through contact with microorganisms from other humans and the natural environment.”

The “Old Friends” theory offers some insight into why exposure to microbes in early childhood may be significant. The theory proposes that the development of proper immune function depends on exposure to micro-organisms that held a constant presence throughout mammalian evolution and that these organisms help stimulate the production of regulatory T cells (Treg ). These micro-organisms do not, in most cases, cause common childhood infections (although they include some intestinal parasites), and yet the hygienic conditions of modern city life and conventional medicine do generally reduce our exposure to them.

In light of all this, using the most potent antimicrobial oils and blends automatically for any and every illness is likely not providing the most appropriate support for a developing immune system and may even hinder its development. In addition, parents are sometimes using the essential oil “big guns” at quite young ages. Babies as young as a few hours old are being exposed to these oils on a consistent basis under the false belief that it is necessary in order to keep them from getting sick. Paradoxically, the child’s innate protection device, its immune system, may be adversely affected.

Roger C Parslow, a member of the Paediatric Epidemiology Group a the Universtity of Leeds sums the whole argument nicely: “Striking the right balance between protecting our children from damaging or life threatening infections whilst exposing them to a ‘sufficient dose’ of milder infections to prime their immune systems has far-reaching social and behavioural connotations.”

Is there any place for potent antimicrobials in wellness care?

Taking into account the cautions expressed above, we could reasonably argue that, yes, there is a time and a place for the use of powerful antimicrobial essential oils (at safe levels). But this does not mean they are always the most fitting choice.

In addition to the potential risk to the immune system that overuse could pose in childhood, oils like lemongrass, cinnamon bark, oregano, thyme thymol, and clove are among the most likely to cause adverse skin reactions. This may be because some of the same mechanisms that kill bacterial cells are also not kind to skin cells. And so, these particular essential oils have topical maximum use levels ranging from 0.1% to 1.3% for adults, and even lower maximums for children. For topical a

pplication, the misuse and overuse of these substances may have a negative impact on the immune system, both in terms of developing immunity and in terms of causing allergic reactions, either immediately or at some future time. The above article points out that although essential oil constituents are generally too small to be recognized by the immune system, the process of haptenation allows for a constituent to get around this limitation and for the body to potentially develop antibodies to it. If this happens, subsequent exposure results in an allergic response as the adaptive immune system has now been conditioned to recognize the constituent as a threat.

Caution also applies to inhalation – the more potent antimicrobial oils can cause irritation and physical discomfort when inhaled, not to mention possible negative impact on thedeveloping immune system as well as still-developing respiratory tracts. Though the risk is lower. Over-diffusion of the strong antimicrobials should therefore be avoided in the case of children. The good news is that this risk can be greatly reduced by adhering to appropriate dilution limits based on the individual oil, as well as limiting topical application to incidents that truly require it. And if you want to mitigate the risk even further, there are other aromatic oils that are much safer to use, although their powers tend to be underestimated. Many times these are a better option, especially when it comes to use with children.

Essential oils of palmarosa, rosemary, marjoram, lavender, tea tree, bergamot, and lemon all show good efficacy against a variety of microbes. Some have extra therapeutic benefits that make them even better option for addressing some of the most common childhood illnesses that can be handled in the home. Not only are they effective antimicrobials, but they also promote relaxation and rest – a crucial aspect of sick care that is all too often glossed over in lieu of searching for killing power. This provides an overall effect that is quite different from the more stimulating phenol-rich or aldehyde-rich oils typically favored as germ fighters, while still providing antimicrobial benefit.

Given this information, it is ideal to select oils with less inherent risks first and treat the “big guns” as one would antibiotics or prescription medications. Chances are that by the time you would reach for them, your child is probably sick enough to need the attention of a medical professional.

It may also be worth using the heavier antimicrobial oils and blends after an illness has run its course as a part home sanitation routine. Run the diffuser for 30-60 minutes behind closed doors away from family members, then shut it off and air out these spaces. To avoid potential overstimulation and reduce exposure, the main living area can be sanitized after children have gone to bed.

Conclusion

The tendency to reach for powerful antibacterial oils is disturbingly similar to issues in recent history with doctors handing out antibiotics whether or not the condition of their patients actually merited their use. Currently, essential oils offer excellent options in fighting the growing issue we face with resistant microbes. As discussed before, we have yet to see the microbial resistance to them, possibly due to the unique composition of each essential oil, with slight variations even within the same species. But this does not mean that microbial resistance to essential oils will never develop, and the current market and culture surrounding essential oils use raises concerns in this matter.

Overuse of essential oils and in particular oils like clove, cinnamon, thyme thymol, oregano, and blends high in these, come with significant risk. While this risk can be reduced through appropriate safety measures, it is best to seek other options when treating children given the potential impact on their body, as well as the long-term concerns about microbial resistance. We can care for our children by performing a diligent assessment and then carefully selecting the most appropriate (and least risky) essential oils for them when ill, and we can help preserve their future wellness by safeguarding how we use oils now.

If you give nature time, it will find a way to overcome obstacles placed in its path – which is true both for bacteria, and for our bodies. With effective options available that are less risky than the “big guns”, using clove, cinnamon, thyme thymol, oregano and similar oils for every little sniffle is tantamount to dumping a gallon of water on a match to extinguish a flame that could have been snuffed out with a little sprinkle. It is, in most cases, quite unnecessary.

References:

AK LECTURES (2014, November 14). Adaptive immune system Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kr9WsHUSnp4&t=3s

Bloomfield, S. F., Stanwell-Smith, R., Crevel, R. W. R., & Pickup, J. (2006). Too clean, or not too clean: The hygiene hypothesis and home hygiene. Clinical Experimental Allergy, 36(4), 402–425. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02463.x

Bloomfield, S.F., Rook, G.A., Scott, E.A. et al (2016). Time to abandon the hygiene hypothesis: new perspectives on allergic disease, the human microbiome, infectious disease prevention and the role of targeted hygiene. Perspectives in Public Health 136(4):213-224. doi:10.1177/1757913916650225.

CDC (1994). Vital and health statistics: health of our nation’s children. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_191.pdf

CDC (2007). National surveillance for asthma – United States, 1980-2004. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5608a1.htm#tab3

CDC (2013). Trends in allergic conditions among children: United States, 1997-2011. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db121.pdf

CDC (2016). Most recent asthma data. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm

CDC (2017). Asthma’s impact on the nation. Data from the CDC National Asthma Control Program. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/impacts_nation/asthmafactsheet.pdf

North, R. J., Berche, P. A., & Newborg, M. F. (1981). Immunologic consequences of antibiotic-induced abridgement of bacterial infection: Effect on generation and loss of protective T cells and level of immunologic memory. The Journal of Immunology, 127(1), 342–346. Retrieved from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/127/1/342

Research, G. V. (2016, December 28). Essence market. . Retrieved from http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/essential-oil-market-size-to-reach-1167-billion-by-2022-grand-view-research-inc-531216151.html

Rook, G. A. W., Adams, V., Palmer, R. et al (2004). Mycobacteria and other environmental organisms as immunomodulators for immunoregulatory disorders. Springer Seminars in: Immunopathology, 25(3-4), 237–255. doi:10.1007/s00281-003-0148-9

Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes, F., & Adib-Conquy, M. (2017). Retrieved 15 May 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3324953/

Strachan, D. P. (1989). Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. British Medical Journal, 299(6710), 1259–1260. doi:10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259

Tisserand, R., Young R., (2014) Essential oil safety: a guide for health care professionals, 2nd edition. London, Churchill Livingstone.

WHO. (2016, February 2). Asthma. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs307/en/

Thank you!!!

While I agree that you should take care with essential oils and their use with children, being so careful that you aren’t using them at all and end up having to take your children to the doctor for antibiotics defeats the purpose. Usually parents and loved ones know how their children and if they need some support with EO’s to get over a bug or not. My niece and nephew were constantly sick, even having the flu twice in one season until we started using essential oils diluted on their feet and diffused, including some of the “big guns”. Diffusion was used particularly when having medical therapists stopping in (who visit other children first carrying in their germs). This alone has stopped much of the sickness they have had in the past. They had many opportunities to build up immunities before this, but it was apparently not enough. So just as I would use antibiotics if needed, even repeatedly, I would also use the oils as needed, even repeatedly, if it meant not ending up back at the doctor’s for more antibiotics or prescriptions to treat symptoms. The point of not over-using oils is good, but it seems a bit too much to say to take such care that you don’t use it and by that time, likely you’ll need to go to the doctor anyway. Most of us don’t want to reach that point. Treating a sickness is what traditional doctors do, preventing it is what functional doctors do, and what I would like more people to do. It’s not enough to treat symptoms, let’s do our best to avoid getting sick in the first place, and sometimes this means pulling out the big guns when you know you’re kids aren’t going to be able to handle it on their own. Don’t overreact, but don’t refuse to use what works for your family either. Educate yourself, be wise, take precautions, dilute properly, don’t overuse, but do use what you need when you need it. That’s my opinion and what works for me and my family.

Thank you and I think it is always worth warning about phototoxicity particularly with Lemon and Bergamot. So many people have no idea about this!!

So great! The mommy world needs articles like this one. I tried sharing it on pinterest and it won’t let me!

This is an interesting article, for many reasons. Primarily the idea that fear drives a parental response to their child being ill and in pain. Yes, a parent will instinctively reach for the nearest medicinal solution. I would offer that a parent is usually tolerant of their child’s illness until it warrants taking time off school or work. That, to me, is a good time to get out the ‘big guns’. The alternative is to take your child to the doctor or pharmacist who will (either to pacify the parent, or with the grim understanding the parent is expecting a solution of some sorts) invariably prescribes paracetamol or ibuprofen or both. Whether the preferred solution be pharmaceutical or plant based, I would offer instead the idea of moving away from the traditional idea of treating a symptom for immediate relief and introduce the holistic approach of time off needed for the body to recover. In this fast paced, instant gratification world we live in, thats practically an act of rebellion.

This is a poorly cited article. Has there been any research at all regarding essential oils altering immune function? Has there been any research at all regarding microbial resistance to essential oils? Please post them instead of speculating. I am looking for real information, not opinion. Also, contact dermatitis can occur with any essential oil. Children need to be monitored after any treatment. Also lacking in this article is any research on beneficial microbes in the gut and their role in immune function. More research needs to be done regarding essential oils impact on beneficial microbes. More research needs to be done on intestinal health as well. https://new.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2016/5436738/

Dear Bethany,

Thank you for your comment. Indeed, a lot more research needs to be done on all the issues you mention, and especially the impact of using essential oils on the gut microbiome. Thank you for posting a link to the paper. We would be interested to hear your thoughts on the paper itself. I suggest checking out Dr. Jason Hawrelak, who is a naturopatic doctor specializing in the microbiome restoration. I’m not sure if he published his research, but he presented his finding at a conference, and Oregano oil showed to be fairly destructive to the gut microflora. http://congress.metagenics.com.au/postcongress/media/presentation-slides/day2-2-jason-hawrelax-treatment-dysbiosis-small-and-large-bowel.pdf see slide 48 and on.

In terms of resistance to essential oils in bacteria, here is a recent piece of research: https://europepmc.org/article/med/31383658

As for safety concerns, yes, technically any essential oil can cause dermal reaction, but the oils that are considered strong antimicrobials (cinnamon bark, clove, oregano) are much more potent in terms of skin irritation as well. It is logical if you think of it – they are known to be good at penetrating cell membranes of bacteria, and this translates to their ability to irritate the skin to a greater level. The difference is in the level of risk one is taking.

I hope this answers your concerns.